Rotational Crestal Flap Associated with PRF: A Novel Technique for Oroantral Communication Closure

Abstract

Oroantral communication can be defined as a pathologic opening created between the oral cavity and the maxillary sinus.

It mostly results from the extraction of upper molars and premolars. If left untreated, it may lead to an oroantral fistula and/

or maxillary sinusitis. Several modalities have been described for the management of this communication. The most employed

surgical flaps involve advanced buccal flap, palatal flap and buccal fat pad flap. Yet, these techniques have shown advantages as

well as limitations. The treatment of oroantral communication using a rotational crestal flap in conjunction with platelet-rich

f

ibrin (PRF) represents an innovative technique that integrates the benefits of PRF with a minimally invasive surgical approach.

Keywords: Oroantral closure, PRF oroantral communication, Soft tissue closure, Rotational crestal flap, Flap technique

1. Introduction

Oroantral communication (OAC) is a common complication resulting from maxillary posterior teeth extraction1. It is frequently encountered by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. It can be described as a pathological opening between the maxillary sinus and the oral cavity2. It is commonly agreed that OAC should be closed within 24 to 48 hours to prevent chronic sinusitis and the formation of fistulas3.

Several techniques have been used for OAC closure, such as mucoperiosteal flaps or buccal fat pad grafts4. Although it is possible to close OACs using these techniques, the difficulty lies in post-surgical prosthetic restoration (removable or fixed) given the decrease of the buccal sulcus depth and the lack of attached gum tissue in the prosthesis surroundings. To deal with these disadvantages, a novel technique consisting of a rotational crestal flap associated with PRF, is presented in this paper.

This technique has several advantages. It allows adherent gum tissue blood supply, helps to avoid the risk of damaging the greater palatal artery and the possible permanent decrease of the buccal sulcus depth, which allows for a fast prosthetic restoration.

2. Case history/examination

A 65-year-old male patient presented to our department suffering from spontaneous and continuous toothache in the left upper maxilla. He was suffering from atherosclerotic coronary heart disease and was treated with platelet aggregation inhibiting drugs (Acetylsalicylic acid). Extraoral examination did not show any particularity. Intraoral examination revealed a red oedematous gum around the 28 that was partially impacted. The vitality test was positive. The tooth did not present any carious lesion or periodontal pocket. Diagnosis of a serious pericoronitis related to the 28 was made and extraction of the tooth was planned.

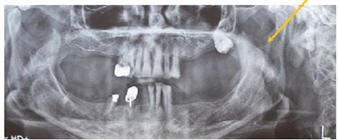

Radiographic examination revealed an inferiorly curved maxillary floor on which the roots of the left maxillary third molar were projected (Figure 1). An Oroantral communication was suspected. The patient did not present any sinus symptoms. He declared that he never had sinusitis. However, panoramic x-ray showed bilateral opacity in the maxillary sinus floor. Endoscopic exploration of the nasal cavity showed a clear middle meatus.

Figure 1: Panoramic X-ray: Yellow arrow showing the roots of the teeth projecting into the maxillary sinus.

The tooth was urgently extracted at the same day and the dental socket was softly inspected using a surgical alveolar curette. Examination showed an oroantral communication that was confirmed by the Valsalva Test: An air flow was noticed in addition to air bubbles getting out of the alveolar socket. The diameter of the communication was about 10mm. It was clinically determined using a surgical alveolar curette and the mirror test. The root depth in the maxillary sinus was about 6mm. It was initially visualized on the panoramic x-ray and then confirmed after the extraction of the tooth (Figure 2). The depth of OAC was about 1 mm (distance between the highest spot on the crest and the sinus floor).

Figure 2: The left maxillary third molar after its extraction.

• Graduated periodontal probe showing the diameter of the communication.

• Dental probe (number 23) showing the depth of the root in the maxillary sinus.

Examination of the mucosa around the dental socket showed the absence of attached gingiva (Figure 3). OAC closure was performed at the same day under local anaesthesia. The patient underwent extraoral antisepsis with povidone iodine solution and intraoral antisepsis with chlorhexidine 0.12%. Infiltration anaesthesia was performed around the dental socket and palate using 4% articaine and epinephrine 1: 100,000.

Irrigation of the sinus with saline through the OAC was carried out. Lavage fluid was clear and did not contain inflammatory exudates. A rectangular gingival flap of total thickness (Figure 4) was raised from the top of the ridge, rotated and buccally sutured to gain attached gingiva (Figure 5).

Figure 5: gingival flap was elevated, rotated and buccally sutured.

A PRF membrane was furnished in the bony defect (Figure 6) and sutured superficially as well on the socket for complete and hermetic closure (Figure 7). Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (Augmentin®) (1 g twice a day), steroidal anti- inflammatory (Nasonex ®) as nasal drops, acetaminophen-codeine (Klipal ®) (600mg twice a day) for pain control and warm saline intraoral mouth rinses with 0.12% chlorhexidine, were prescribed. The patient was instructed to avoid vigorous sports and activities that may produce pressure changes. No post-operative complications were observed and complete wound healing was noted after one month. A gingival nodule was noted at the base of the gingival flap due to its rotation (Figure 8). This nodule was deepithelialized.

Figure 6: closure of the dental socket by the PRF membrane.

Figure 7: suture of the second PRF, superficially

Figure 8: clinical picture showing full closure of the communi cation one month after the surgery. Note the gingival nodule at .the base of the gingival flap

3. Conclusions and Results

One week later, mucosal examination showed a conservation of the buccal sulcus depth (Figure 9a) and a 3mm gain of adherent buccal gingiva (Figure 9b). The impression of the patient’s removable denture was taken the same day. He was able to wear it two weeks later. The removable denture was retentive (Figure 10a, Figure 10b).

Figure 9: Seven weeks after the surgery (photo taken by a mirror)

a: Note the conservation of the buccal sulcus depth b: note the gain of 3mm of adherent buccal gingiva.

Figure 10: a-b: Retentive removable partial denture in mouth (Photo taken by a mirror).

4. Discussion

Oroantral communication can be defined as a pathologic opening created between the oral cavity and the maxillary sinus. It is mostly the result of the extraction of upper molars and premolars. If left untreated, it may lead to an oroantral fistula and/or maxillary sinusitis.

The clinical decision making with regard to OAC closure is related to multiple factors, including the size, the presence of maxillary sinusitis and the time of diagnosis.

OAC with a 2-mm diameter or less have a high chance of spontaneous recovery while larger defects normally necessitate surgical techniques due to the elevated risk of maxillary sinus inflammation associated with large bony defects4,5.

OAC closure has been managed using a variety of strategies, including local and soft tissue flaps. Grafts, such as autografts, xenografts, allografts, alloplastic products and other approaches, such as guided tissue regeneration (GTR) or rapid implantation of a dental implant are examples of such therapies6.

Buccal advanced flap (BF) was introduced by Rehrman in 1936. For the closure of small communication or minor fistulas that need simple suturing, surgeons often prefer this procedure as the first line of treatment6. In this technique, 2 diverging vertical incisions from the extraction site to the buccal vestibule are performed; then, the trapezoid mucoperiosteal flap is raised and positioned over the defect. This flap ensures a high survival rate and a sufficient blood supply. However, it also has a major disadvantage. Indeed, the buccal sulcus depth might be shortened, leading to a decrease in retention and a discomfort for patients with dentures7.

The buccal sliding flap was introduced by Moczair. It is now considered an alternative method for closing OAC6. By shifting the flap one tooth distally, this technique has the advantage of minimizing the effect of losing the buccal sulcus depth. However, since a considerable amount of dento-alveolar detachment is required to promote distal sliding, periodontal disease and gingival recession can develop6,7.

The palatal full thickness flap was introduced by Ashey to close oro-antral communications. The palatal fibro-mucosa is incised so as to raise a flap with posterior base, which is supplied by the greater palatine artery8. The anterior extension of the flap must be large enough to exceed the diameter of the bony defect and long enough to allow lateral rotation. Suturing should be performed without tension8. Its major advantage is the supply of gum attached tissue to the receiving site. This technique also allows denture wearing a short time after the wound healing. Moreover, using this technique allows the buccal sulcus depth to be kept intact9. However, the drawbacks of this technique involve the risk of damaging the blood supply, the difficulty of dissection and the need for a skilled surgeon10.

The buccal fat pad (BFP) is a fatty tissue enclosed by a thin f ibrous capsule in a lobulated shape that is found in the Oro maxillofacial area and it has been used for OAC closure. The advantages of this technique include sufficient blood supply, high success rate, decrease in the infection risk, rapid epithelialization of the uncovered fat, minimal donor site morbidity and the possibility to close medium-sized defects of the maxilla9,11.

Despite these benefits, when used to close major defects, the BFP may show graft necrosis and new fistulas. In addition, when deciding on the type of procedure to be used, the surgeon’s skill and expertise should be taken into consideration. In fact, the using this technique requires very careful manipulation. Moreover, this approach does not allow bone regeneration, which makes implant restoration afterwards impossible12,13. Also, this technique cannot increase the amount of attached gingiva which plays an important role in the durability of fixed prostheses as well as the retention of removable prostheses.

Plasma-rich fibrin technique is an effective method, which can be used in the closure of OACs with a 5-mm or smaller diameters with a little risk of complications. It offers many advantages, such as enhancing soft tissue healing, reducing inflammatory complications, increasing bone width, decreasing bone resorption and reducing alveolar osteitis. It also has the advantage of reducing pain and swelling compared to buccal advancement flap. This technique can be combined with bone grafts in case of a restoration in which implants are planned. The use of PRF totally covers the bone graft, thus preventing mesh exposure and bone resorption.

Given the shortcomings of local buccal flaps, palatal flaps and buccal fat pads in closure of OAC, we present a novel alternative technique combining rotated crestal gingival flap with PRF. Rotational crestal flap combined with PRF combines the advantages of palatal flap, buccal advancement flap (BAF), fat pad flap (FPF) and PRF. It is a quick, simple and secure procedure since it avoids the risk of damaging the large palatal artery observed in the palatal flap. It allows the supply of gum attached tissue to the receiving site. It also preserves the buccal sulcus depth, which allows a possible and rapid denture confection. Moreover, it reduces pain and swelling compared to other techniques (BAF and FPF) and decreases the risk of infections due to the anti- inflammatory properties of PRF. It is also important to note that the use of PRF stimulates angiogenesis and re-epithelialization, leading to a fast healing. However, this technique presents two major disadvantages. The f irst disadvantage is the postoperative pain in the site of the raised f lap due to the uncovered bone, which could be overcome using a partially thickness flap. The second one lies in the formation of a nodule at the base of the flap due to its rotation, necessitating desepithelization.

5. Conclusion

Rotational crestal flap associated with PRF is a novel and reliable option for repairing small and medium-sized OAC. This technique must be considered for OAC closure in patients with posterior edentulism for whom prosthetic restoration with a removable denture is scheduled. It preserves the vestibule depth and allows a supply of attached gingiva to the receiving site. The latter plays an important role in the durability of fixed prostheses and in the retention of removable prostheses. When restoration with implants is planned, this technique can be associated with bone graft.

6. References

1.Ossama H, Shoukry T, Raouf AA, et al. 1 Combined palatal and buccal flaps in oroantral fistula repair. Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied Sciences, 2012;13: 77-81.

2.Haas R, Watzak G, Baron M, et al. 3 A preliminary study of noncortical bone grafts for oroantral fistula closure. 11 Oral Surgery oral Medicine oral Pathology oral Radiology and Endodontology, 2003;96: 263-266.

3.Von Wowern N. Frequency of oro-antral fistulae after perforation to the maxillary sinus. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 1970;78: 394-396.

4.Abuabara A, Cortez ALV, Passeri LA, et al. Evaluation of different treatments for oroantral/oronasal communications: experience of 112 cases. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2006;35: 155-15

5.Shishir M, Hasti K, Bhupendra H. The use of the buccal fat pad for reconstruction of oral defects: review of the literature and report of cases. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery, 2012;11: 128-131.

6.Wang MN. Closure of oroantral fistula. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 1988;17: 110-115.

7.Kwon M-S, Lee B-S, Choi B-J, et al. Closure of oroantral fistula: a review of local flap techniques. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 2020;46: 58.

8.Rintala A. A double, overlapping hinge flap to close palatal fistula. Scandinavian journal of plastic and reconstructive surgery, 1971;5: 91-95.

9.Borgonovo AE, Berardinelli FV, Favale M, et al. Surgical options in oroantral fistula treatment. The open dentistry journal, 2012;6: 94.

10.Dergin G, Emes Y, Delilbasi C, et al. Management of the Oroantral Fistula. A Textbook of 15 Advanced Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 2016;3: 3367.

11.Batra H, Jindal G, Kaur S. Evaluation of different treatment modalities for closure of oro-antral communications and formulation of a rational approach. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery, 2010;9: 13-18.

12.Parvini P, Obreja K, Begic A, et al. Decision-making in 3 closures of oroantral communication and fistula. International journal of implant dentistry, 2019;5:

13.Tideman H, Bosanquet A, Scott J. Use of the buccal fat pad as a pedicled graft. 9 Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery: official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 1986;44: 435-440.

.