A Rare Primary Inferior Lumbar Hernia Treated by Transperitoneal Laparoscopy: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

Background

Lumbar hernias are rare defects of the posterior

abdominal wall, accounting for less than 2% of all abdominal hernias, with

fewer than 400 cases reported in the literature. They arise through anatomical

weak points—either the superior (Grynfelt-Lesshaft) or inferior (Petit) lumbar

triangles-and often present a surgical challenge due to the limited

availability of healthy tissue for reconstruction. Advances in minimally

invasive surgery have made laparoscopic repair, through either a

transperitoneal or extraperitoneal approach, an increasingly preferred option.

Case Presentation

We report the case of a 56-year-old man with diabetes

who presented with a painful, reducible swelling in the left lumbar region. He

had no history of trauma, prior surgery or bowel obstruction. Physical

examination revealed a soft, non-inflammatory mass. Abdominal CT scan

demonstrated a left lumbar hernia measuring 38 × 81 mm, with a 26-mm neck and

containing only fat. Given the symptomatic presentation and favorable anatomy,

a transperitoneal laparoscopic repair was performed. After mobilization of the

descending colon from the abdominal wall, the defect was identified and closed

with sutures. A 15 × 20-cm mesh was placed to reinforce the repair and secured

using 5-mm absorbable laparoscopic tacks. The postoperative course was

uneventful and the patient was discharged on postoperative day three without

complications.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the safety and effectiveness of

the transperitoneal laparoscopic approach for primary lumbar hernia repair.

Laparoscopy provides excellent anatomical visualization, allows secure mesh

placement and is associated with reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital

stay and rapid recovery. As demonstrated in this patient, minimally invasive

repair represents a valuable option for the management of both primary and

acquired lumbar hernias.

Keywords: Lumbar hernia; Inferior lumbar triangle; Laparoscopic

repair; Transperitoneal approach; Abdominal wall hernia; Rare hernia

Introduction

Lumbar

hernias are rare defects of the posterior abdominal wall, accounting for less

than 1-2% of all abdominal wall hernias1.

The first description of a lumbar hernia was reported by Barbette in 16722. These hernias occur when intra-abdominal,

intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal contents protrude through an area of

weakness in the posterior abdominal wall.

Anatomically,

lumbar hernias are classified according to the location of the defect: superior

(Grynfeltt–Lesshaft triangle) or inferior (Petit’s triangle). They may be

congenital or acquired, the latter being more common3.

Diagnosis

is often suggested clinically but is best confirmed by computed tomography

(CT), which allows precise assessment of the defect and helps differentiate it

from other masses. Surgical repair is the treatment of choice. However, repair

can be challenging due to the limited local tissue for reinforcement and the

proximity of bony structures. Both open and laparoscopic techniques have been

described, including transabdominal and extraperitoneal approaches.

Herein,

we report a case of a spontaneous inferior lumbar hernia successfully treated

by a transperitoneal laparoscopic approach.

Case Report

A

56-year-old man with a medical history of diabetes presented with a gradually

enlarging left lumbar swelling associated with effort-related pain. He had no

gastrointestinal symptoms, no signs of bowel obstruction and no history of

trauma or prior surgery in the lumbar region.

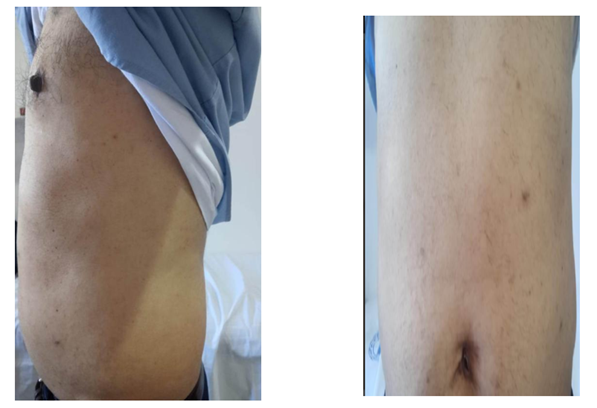

Physical

examination revealed a soft, reducible left lumbar mass without inflammatory

signs (Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2: a soft, reducible left lumbar mass without inflammatory signs, measured 80 mm

A

contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan demonstrated a 38 × 81 mm left lumbar

hernia containing adipose tissue. The hernia neck measured 26 mm and no

visceral content was noted (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure

3: (Computed tomography scan coronal view) Figure 4: (Computed tomography scan

axial view)

Figures

3, 4: A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan demonstrated a 38 × 81 mm left

lumbar hernia containing adipose tissue. The hernia neck measured 26 mm and no

visceral content was noted

Given

the reducibility of the hernia and the patient’s symptoms, a laparoscopic

transperitoneal repair was planned. The patient was positioned in a

semi-lateral decubitus position. Three trocars were placed: subxiphoid,

periumbilical and suprapubic. The descending colon was carefully mobilized off

the lateral abdominal wall due to its proximity to the defect (Figure 5).

Figure

5: Trocars placement

The

hernia orifice was clearly identified and closed with non-absorbable sutures. A

15 × 20 cm prosthetic mesh was positioned to reinforce the defect and secured

using 5 mm absorbable laparoscopic tacks (Figures 6-10).

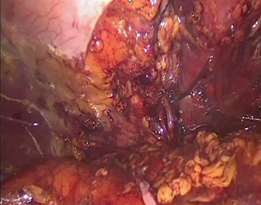

Figure

6: Intra operative view of the lumbar hernia. The hernia orifice was

clearly identified

Figures

7,8: The hernia orifice was identified and closed with non-absorbable

sutures

Figure

10: A 15 × 20 cm prosthetic mesh was positioned to reinforce the defect and

secured using 5 mm absorbable laparoscopic tacks

The

postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on

postoperative day 3. At six-month follow-up, he remained asymptomatic with no

evidence of recurrence (Figure 11).

Figures

10, 11: The result after 6 months of follow-up with no recurrence

Discussion

Lumbar

hernias are an uncommon form of abdominal wall defect, representing less than

1–2% of all abdominal wall hernias4.

They tend to occur more frequently in men and are reported predominantly on the

left side, although the reasons for this lateral predominance remain unclear3. Anatomically, the posterior abdominal

wall contains two areas of natural weakness that predispose to herniation. The

superior lumbar triangle (Grynfeltt-Lesshaft triangle) is bounded superiorly by

the 12th rib, medially by the quadratus lumborum muscle and laterally by the

posterior border of the internal oblique muscle. Its floor is formed by the

transversalis fascia, while the roof consists of the external oblique muscle.

The inferior lumbar triangle (Petit’s triangle), by contrast, is defined

anteriorly by the external oblique muscle, posteriorly by the latissimus dorsi

muscle and inferiorly by the iliac crest. Weakness within either of these

anatomical triangles may allow retroperitoneal or intraperitoneal contents to

protrude, giving rise to a lumbar hernia. Understanding the structural

boundaries and intrinsic vulnerabilities of these regions is essential for

accurate diagnosis and for planning the most appropriate surgical approach.

Etiology

Lumbar hernias may be congenital, representing

about 20% of cases or acquired, accounting for nearly 80% of all presentations5. Acquired lumbar hernias are further

classified as either primary or secondary. Primary (spontaneous) hernias

develop without any preceding trauma or surgery and are often associated with

factors such as aging, chronic increases in intra-abdominal pressure, chronic

cough, heavy lifting, obesity or extreme thinness. In contrast, secondary

hernias arise as a consequence of trauma, previous surgical

procedures—particularly iliac crest bone graft harvesting-local infections or

muscle atrophy. In the present case, the patient exhibited none of the

predisposing events or surgical history typically associated with secondary

hernias, supporting the diagnosis of a primary spontaneous lumbar hernia.

Clinical presentation

Patients with lumbar hernias may present with

nonspecific or subtle symptoms, which often contribute to delayed diagnosis and

misinterpretation. The most frequent clinical finding is a soft, posterolateral

swelling in the lumbar region that may increase with coughing or straining and

may or may not be reducible. Some patients report vague, intermittent lower

back or flank pain due to traction on surrounding tissues. Although

incarceration or strangulation is considered uncommon, several authors have documented

these complications, emphasizing the importance of early detection and

appropriate management1,2.

Because their presentation may resemble more common conditions-including

lipomas, abscesses or soft-tissue tumours-lumbar hernias require a high index

of suspicion for accurate diagnosis3.

In our case, the patient presented with a well-defined swelling located in the

inferior lumbar triangle on the left side, progressively enlarging over one

year.

Diagnosis

Although

the diagnosis may be suggested clinically, CT scan remains the gold standard

imaging modality. It provides detailed information regarding the size of the

defect, content of the hernia sac and helps exclude differential diagnoses such

as lipoma, rhabdomyoma, hematoma or sarcoma6.

In

our case, the CT scan demonstrated a well-defined posterolateral defect located

in the inferior lumbar triangle on the left side, with protrusion of

preperitoneal fat into the subcutaneous tissues. The hernia sac contained no

bowel loops and there were no signs of incarceration or inflammatory changes.

The detailed CT findings confirmed the diagnosis of a primary lumbar hernia and

guided the surgical strategy by clearly illustrating the dimensions of the

defect and its relationship to adjacent muscular structures.

Management

Due to the potential risk of complications-most

notably incarceration-surgical repair is generally recommended for both primary

and secondary lumbar hernias7.

The main objective of the intervention is to restore the integrity of the

abdominal wall, reinforce the weakened anatomical zone and minimize the

likelihood of recurrence. However, repair of lumbar hernias can be technically

demanding because of several anatomical constraints. The defect lies between

rigid osseous boundaries, namely the 12th rib superiorly and the iliac crest

inferiorly, which limit surgical exposure and restrict the placement of

fixation points. Additionally, the musculature in this region is often

attenuated or anatomically deficient, reducing the quality of the available

tissue for primary closure. Achieving sufficient mesh overlap is another

critical challenge, as the confined space and proximity to neurovascular

structures require careful dissection and precise positioning8.

A variety of operative strategies have been

described, ranging from direct tissue approximation and the use of rotational

muscle flaps to the more widely adopted mesh-based tension-free repairs9-11. Both open and laparoscopic approaches

have demonstrated favourable outcomes, yet no standardized technique has been

universally endorsed, largely because of the rarity of lumbar hernias and the

consequent lack of large comparative studies7.

As a result, the choice of surgical method is often individualized, taking into

account the size and location of the defect, the condition of surrounding

tissues and the surgeon’s expertise.

In our case, the hernia was repaired using an

laparoscopic approach with placement of a prosthetic mesh, allowing for secure

reinforcement of the defect and an uneventful postoperative recovery.

Laparoscopic

repair

In

recent years, laparoscopic repair has gained significant popularity in the

management of lumbar hernias, with both the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP)

and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approaches demonstrating promising outcomes12. These minimally invasive techniques

offer several advantages over traditional open repair. The laparoscopic view

provides superior visualization of the anatomical structures, particularly the

boundaries of the lumbar triangles and the extent of the muscular defect, which

facilitates precise dissection and safer manipulation of surrounding tissues.

Because laparoscopic repair requires only minimal dissection, it reduces trauma

to the abdominal wall and lowers the risk of postoperative morbidity.

Another

major benefit is the ability to achieve optimal mesh placement with generous

overlap, ensuring secure coverage of the defect and reducing the likelihood of

recurrence. The minimally invasive nature of these techniques is also

associated with less postoperative pain, a lower incidence of surgical site

infections and hematomas and reduced need for postoperative analgesia13-15. Additionally, patients typically

experience a shorter hospital stay and can resume normal activities more

quickly compared to those undergoing open surgery, making laparoscopy an

attractive option whenever feasible.

In

our patient, the transperitoneal laparoscopic approach allowed safe

mobilization of the descending colon, clear visualization of the defect and

secure mesh placement. The postoperative outcome was excellent, with no

recurrence at 6 months.

Conclusion

Lumbar hernias are rare and can be easily

overlooked due to their subtle presentation. Early surgical repair is

recommended to prevent complications such as incarceration or strangulation.

The proximity of bony landmarks and the weakness of the posterior abdominal

musculature make repair technically challenging.

Laparoscopic lumbar hernia repair is a safe and

effective approach offering superior visualization, reduced postoperative pain

and faster recovery. Although no standardized surgical technique exists due to

the rarity of this condition, laparoscopic transperitoneal repair represents a

valuable and increasingly preferred minimally invasive option.

References

3. Gaillard F, El-Feky M, Rasuli B, et al. Lumbar hernia.

Reference article Radiopaedia.

7. Sharma P. Lumbar hernia. MJAFI 2009;65:178–179

9. Geis WP, Hodakowski GT. Lumbar hernia. In: Nyhus LM,

Condon RE (ed) Hernia. Lipincott, Philadelphia 1995:412-424.

14. Sundaramurthy S, Suresh HB, Anirudh

AV, Rozario AP. St. John’s Medical College Hospital, Department of General

Surgery, Sarjapur Road, Koramangala, Bangalore, Karnataka Primary lumbar

hernia: A rarely encountered hernia Sharada 2015.