Balloon Dilation in Septal Surgery: An Experimental Analysis of Unguided Balloon Motion

Abstract

Key

Points

• Unguided

nasal balloons displace with unintended motion at a critical angle of ~5

degrees.

• Closer

plate spacing increases balloon migration even at small angles, amplifying

instability.

• Results

support guided dilation systems to limit unintended forces on critical anatomy.

Keywords: Nasal surgery; Balloon dilation; Mechanical phenomena;

Equipment design; Endoscopy/methods

Introduction

Balloon

sinus dilation (BSD) represents a minimally invasive technique used in

sinonasal procedures to improve sinus patency without extensive mucosal

disruption1. The popularity of

BSD influenced the development of balloon-assisted septoplasty (BAS) techniques

to minimize dissection while providing access for FESS and other transnasal

procedures. One common FDA-approved septal mobilization balloon is the Relieva Tract

Balloon Dilation System, an unguided 16x40 mm balloon2.

Multiple

studies cite favorable safety outcomes, reflecting the growing popularity of

unguided balloons (UGB)3. Rare

complications of CSF leaks and orbital injuries are reported4-7. UGBs’ expansion between nonparallel

surfaces create uneven force vectors and unintended motion in the nasal cavity,

with the septum on one side and the lateral nasal wall and inferior turbinate

on the other. This asymmetry creates uneven force vectors, causing unintended

motion, a phenomenon consistent with complications in MAUDE analyses.

Despite

widespread use of UGBs, limited quantitative data exists regarding how surface

angle, spacing and friction influence balloon motion during dilation. Similar

mechanical concerns are described in Eustachian tube balloon dilation

procedures8. Guided balloons have

emerged, addressing these issues by improving control and reducing unwanted

motion9. However, to our

knowledge, this pattern of angle-dependent instability during nasal balloon

dilation has not been previously characterized in the published literature.

This study presents a controlled benchtop evaluation of UGB motion to determine

how these variables affect displacement and to identify the critical angle at

which stability is lost.

Methods

Testing

apparatus

The

experimental apparatus consisted of two 5 x 5-inch steel plates mounted on

threaded rods and spaced precisely with steel nuts and spacing washers. The

plates were lined with 3.25mm of 38A platinum-cure silicone to provide a

uniform elastic surface approximating soft tissue compliance.

Balloon

and inflation system

A

16 mm x 40 mm high-pressure non-compliant nylon balloon was used for all tests.

The balloon was inflated to a maximum pressure of 8 ATM using a 25cc

quick-latch inflation device capable of 30 ATM.

Experimental

procedure

The

plates were first aligned parallel, then adjusted to create varying surface

angles by inserting spacer washers at the upper bolts. The inferior plate

distance remained constant. The balloon was positioned in the lower portion of

the silicone-lined space and inflated initially to 1.5 ATM using manual plunger

action, then to the maximum recommended pressure using the threaded piston

screw mechanism.

Two

dry and lubricated surface conditions were tested with a water-based surgical

lubricant to simulate mucosal conditions. Each configuration was tested in five

consecutive trials (total=65 trials). Angles and distances were measured before

and after inflation using digital calipers.

High-resolution

video documentation was used to record balloon displacement and motion

patterns.

Results

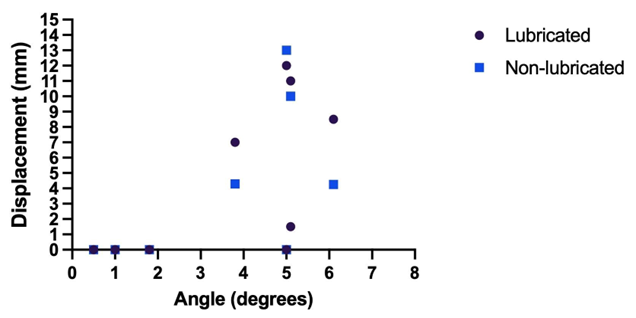

Unguided

balloon displacement began when the surface angle reached approximately 5° from

parallel, with motion increasing as the angle widened. Angles were

progressively widened from 0 to 6.1, with a median value of 5.05° [4.7-5.35].

No movement was observed below 2°. At 5°- 6°, displacement ranged from 1.5 to

13 mm, with initial plate spacing of 8 mm. Consistent motion occurred at angles

of 5° or greater. Lubrication increased travel distance but not occurrence.

Median displacement was 7.15 [3.54-10.51] and 7.75 [4.0-10.381] for

non-lubricated and lubricated, respectively. At a 3.7°-angle, when plate

spacing was reduced to 6.94 mm, 3 mm and 2.51 mm, balloon movement increased. A

nonparametric Wilcoxon analysis confirmed a statistically significant

difference (Wstat =0, Wcritical =5 [~p<0.01]). (Figure 1) summarizes

the displacement trends with respect to angle with each point representing the

average of 5 trials, for a total of 65 trials.

Figure

1: The displacement trends with respect to angle with each point

representing the average of 5 trials, for a total of 65 trials

Discussion

This

study establishes a framework for understanding UGB mechanics in sinonasal

procedures. Our findings revealed a consistent threshold of approximately 5° of

angular divergence between opposing surfaces, at which a high-pressure nasal

balloon transitioned from static to dynamic behavior. Beyond this threshold,

the balloon consistently migrates towards the wider gap, regardless of

lubrication conditions. Narrower plate spacing further amplified this effect,

suggesting that confined anatomical spaces like the nasal cavity may promote

UGB migration, even when tissue planes appear nearly parallel.

The

identification of a critical angle for motion has important implications for

device stability.

Displacement

became more pronounced at reduced spacing, indicating that the narrow septal

corridors encountered clinically can amplify balloon instability. Surface angle

and spacing were the primary determinants of displacement.

The

clinical relevance of these findings is underscored by the number of

complications reported with sinus UGB systems. Analysis of the FDA MAUDE

database has documented over 200 adverse events associated with balloon

sinuplasty devices (Acclarent, Entellus, Medtronic) including CSF leaks,

epistaxis, internal carotid artery dissections orbital swelling necessitating

emergency canthotomy and four periprocedural deaths. Of these complications,

17.8% were related to imprecise catheter movement and 39.6% to guide catheter

malfunction7. The predictable 5°

critical angle provides a mechanical explanation for these events, emphasizing

the need for device stability in confined anatomy.

These

results highlight the need for angle-aware, guided balloon systems. Devices

with rigid guiding elements, such as the ClearPathTM nasal balloon with a guide

spatula, redistribute forces medially and shield lateral structures, directly

addressing the angle-dependent instability revealed in this model10. In a recent study of endoscopic

eustachian tube balloon dilations, surgeons used image-guidance integration for

continuous catheter tracking and no major complications occurred9.

This

benchtop model simplifies complex in vivo anatomy. Rigid steel plates lined

with silicone do not fully replicate tissue compliance, surface irregularity or

mucosal friction. Additionally, the experimental pressures and spacing

distances, while clinically relevant, do not account for dynamic tissue

deformation or capillary adhesion. Cadaveric and computational models are

necessary to validate these findings in more realistic anatomical conditions.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors self-funded this study.

Financial Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of financial

disclosures or conflicts of interests to declare.

Reference

1. Fijałkowska-Ratajczak T, Kopeć

J, Leszczyńska M, Borucki Ł. Balloon sinuplasty in one-day surgery. Wideochir Inne Tech

Maloinwazyjne 2021;16(2):423-428.

2. MAUDE

Adverse Event Report: Acclarent, Inc. Relieva tract balloon dilation system,

16X40MM - 1PK; balloon 2025.

3. Liang X, Lan H, Liang X, et

al. Efficacy and safety of sinus balloon catheter dilation versus functional

endoscopic sinus surgery in the treatment of chronic sinusitis: A

meta-analysis. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2025;104(24):e42841.

4. Lofgren DH, Brandon B Knight,

Shermetaro CB. Contemporary Trends in Frontal Sinus Balloon Sinuplasty: A Pilot

Study. Spartan Med Res

J 2024;9(3):123407.

5. Chaaban MR, Rana N,

Baillargeon J, et al. Outcomes and Complications of Balloon and Conventional

Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Am

J Rhinol Allergy 2018;32(5):388-396.

6. Sayal NR, Keider E, Korkigian

S. Visualized ethmoid roof cerebrospinal fluid leak during frontal balloon

sinuplasty. Ear Nose

Throat J 2018;97(8):34-38.

7. Hur K, Ge M, Kim J, Ference

EH. Adverse Events Associated with Balloon Sinuplasty: A MAUDE Database

Analysis. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 2020;162(1):137-141.

8. Chisolm PF, Hakimi AA, Maxwell

JH, Russo ME. Complications of eustachian tube balloon dilation: Manufacturer

and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database analysis and literature

review. Laryngoscope

Investig Otolaryngol 2023;8(6):1507-1515.

9. Choi SW, Lee SH, Oh

SJ, Kong SK. Navigation-Assisted Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty for Eustachian

Tube Dilatory Dysfunction. Clin

Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2020;13(4):389-395.

10. Brenner MJ, Shenson JA, Rose

AS, et al. New Medical Device and Therapeutic Approvals in Otolaryngology:

State of the Art Review 2020. OTO Open 2021;5(4).