Intrahepatic Subcapsular Hematoma Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the gold standard

treatment for symptomatic gallstones, with an overall morbidity rate of less

than 7%. However, rare but potentially lifethreatening complications can occur,

such as intrahepatic subcapsular hematoma (ISH), which is reported in less than

1% of cases.

Case Report

We report the case of A 30-year-old woman with no

prior medical history, who underwent LC two months after an episode of

gallstone-induced acute pancreatitis. She was discharged the day after surgery

but returned on postoperative day two for a subcapsular hematoma. CT scan

showed an ISH with no evidence of any intra-abdominal haemorrhage. Since the

patient was stable, we opted for serial monitoring in the ICU and conservative

treatment. the patient was discharged the third day with no further complications.

Conclusion

ISH is a very rare but potentially life-threatening

complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This case highlights the

importance of considering this uncommon condition in patients experiencing

abdominal pain after LC, emphasizing that prompt and accurate diagnosis and

treatment are essential for patient survival.

Keywords: Subcapsular liver hematoma; Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy; Complication

Introduction

Since

the first surgical removal of the gallbladder performed in the second half of

the 19th century, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) remains the gold standard

treatment for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis patients with an overall

morbidity of less than 7%1-3.

Complications

of LC include iatrogenic bile duct injury, postoperative bleeding, bowel

injuries and infections. Intrahepatic subcapsular hematoma (ISH) is a rare

complication following LC occurring in less than 1%, however it can prove to be

life-threatening2-4.

Case Report

We present the case of a 30-year-old female,

with no medical history, such as systemic disease or any recent prescription,

who underwent a vaginal delivery 6 months ago and presented a gallstone acute

pancreatitis (Figure 1) 2 months prior to a laparoscopic cholecystectomy

(LC) (Figure 2).

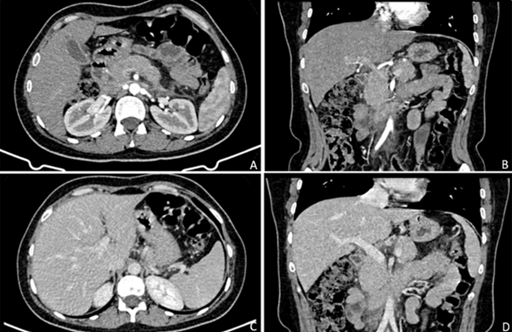

Figure

1: Pre-operative CT scan showing an acute pancreatis. No angioma, tumor or

vascular malformation were apparent

(A)

Arterial phase axial maximum intensity projection; (B) Arterial phase coronal

maximum intensity projection; (C) Portal venous phase axial maximum intensity

projection ; (D) Portal venous phase coronal maximum intensity projection

The patient was discharged at post-operative

day one, however on the second day after surgery, she presented to our

department with severe abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed a

tenderness in the right hypochondrium, hypotension and tachycardia at 130 beats

per minute.

We performed biological tests, that showed a

severe anemia with hemoglobin levels at 5g/Dl. Platelet count and coagulation

profile were within the normal range.

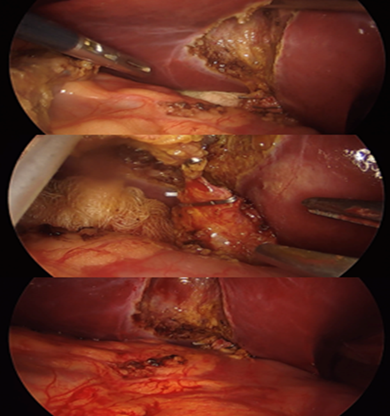

Figure 2: Per-operative view of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. No

complications or adverse event were observed intra-operatively

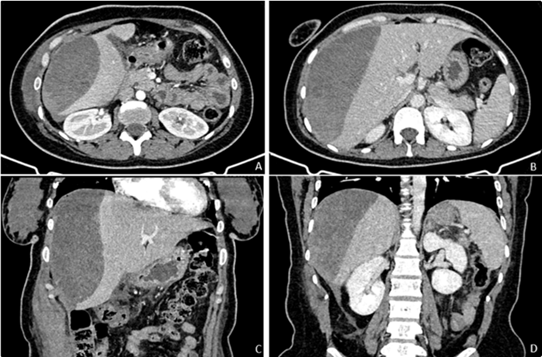

The patient underwent an abdominopelvic CT scan

which revealed a large subcapsular hematoma surrounding the lateral surface of

the right lobe, the hepatic artery, portal vein and hepatic veins opacified

normally and no contrast extravasation was visualized.

The patient was monitored in the UCI and after

being transfused, she stabilized, which prompted monitoring and surgical

abstention.

The patient was discharged on the third day

upon stabilization with no further complications (Figure 3).

Figure

3: post-operative CT scan showing a subcapsular hematoma surrounding the

lateral surface of the right hemi liver, with no active bleeding or ruptured

capsule

(A)

Arterial phase axial maximum intensity projection; (B) Portal venous phase

axial maximum intensity projection ; (C+D) Portal venous phase coronal maximum

intensity projection

Discussion

LC is considered a safe procedure with an

overall morbidity of less than 7% in large cohort studies. Complications after

laparoscopic cholecystectomy occur in 2–6% of patients and bleeding is observed

in less than 1% of cases. The most frequent sites of bleeding after

laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) include the gallbladder bed, cystic artery,

trocar insertion points, falciform ligament and liver capsule tears. Although

intrahepatic subcapsular hematoma (ISH) is a rare complication following LC, it

poses a serious risk due to the potential for rupture and resulting hemodynamic

instability. When rupture occurs into the peritoneal cavity, the associated

mortality rate can reach 75%. These hematomas are typically found on the right

side of the liver. (in 75% of cases)1,2,5,6.

ISH may occur early, up to 24 hours after

surgery, as well as late, several weeks after the procedure1,7.

Some contributing factors have been described,

including iatrogenic injuries of the liver parenchyma and capsular tears,

during gallbladder traction or due to trocar placement. The presence of a

pre-operative pseudoaneurysm or a hepatic haemangioma that could be injured

during the procedure. Perioperative administration of nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) was reported in a number of cases of ISH

following LC with special emphasis on ketorolac use as it was associated with

the highest risk estimate of bleeding. The consumption of NSAIDs in the

postoperative period has also been proposed as an associated cause, since in

several cases the patient used ketorolac (up to 58.8%) or parecoxib in the

postoperative period. It has also been associated with anticoagulant therapy2,8,9.

Our patient, had no specific underlying cause,

as she had no coagulation disorders nor she was taking anticoagulants or

antiplatelet therapy. Furthermore, there was no bleeding source identified nor

a liver parenchymal injury identified throughout the surgery. there was also no

evidence of any hepatic haemangiomas, adenoma or tumour in the preoperative CT

scan performed 2 months prior to the LC. As a matter of fact, there are some

cases where the cause of post cholecystectomy ISH remains unexplained2,3.

16 cases of ISH after LC were reported from

1994 to 2015. Nearly half of the patients presented a hemodynamic instability.

All reported cases involved female patients, with ages ranging from 25 to 78

years. The majority of hematomas were located in the right hepatic lobe, with

some extending into the left lobe. At the time of diagnosis, only one case had

ruptured. Hepatic capsule laceration was found in two cases, one of whom also

took NSAIDS for pain management, Notably, 35.3% of the patients had no identifiable

risk factors3.

Patients with ISH can present in the

postoperative course with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, fever,

hypotension and tachycardia that does not improve with the administration of

intravenous fluids. Patients may also present with hemodynamic instability if a

rupture of the ISH has occurred with intraabdominal bleeding. Furthermore, an

infected hematoma may occur whereby the patient may present with fever,

abdominal pain or some features of sepsis. The time of occurrence in the

previously reported cases varies between 7 hours and 6 weeks of the

postoperative course. On ultrasound or CT scan, it appears as a collection of

fluid between the fibrous and serous layer of the liver2,8,9.

Depending on the patient’s symptoms and

condition, different therapy can be introduced from expectant management to

emergency surgical treatment1.

When the ISH is small, it is usually

asymptomatic, however, if it keeps growing, some complications may occur3.

The management of large ISH remains unclear,

however several strategies have been proposed, such as conservative management

with strict clinical observation, surgical management (laparotomy or

laparoscopy), percutaneous drainage or endovascular embolization. The choice is

conditioned by the patient’s clinical status, the size and cause of the

hematoma2,8.

As there is no clear management pattern because

of the few clinical cases reported, some authors proposed a conservative

treatment for two patients who developed a delayed ISH with fever. One patient

underwent computed-tomography-guided drainage and the other was managed

conservatively without any surgical or radiological procedure10,12-14.

Another author proposed a relaparoscopy for a

hemodynamically unstable patient who had a ruptured ISH with active bleeding

which was evacuated and controlled laparoscopically. One patient underwent

emergency laparotomy, evacuation and drainage of the ISH, which was probably

caused by an instrumental stab wound during LC10,14,15.

When an intrahepatic subcapsular hematoma (ISH)

is small, confined beneath the hepatic capsule and not associated with

intra-abdominal bleeding, conservative management is typically the preferred

approach. This involves careful monitoring of the hematoma over time. If the

hematoma becomes infected, percutaneous drainage under CT or ultrasound guidance,

along with appropriate antibiotic therapy, is the treatment of choice. In cases

involving a ruptured aneurysm, hepatic adenoma or angioma, selective embolization

of the bleeding vessel may be considered. More invasive interventions, such as

relaparotomy or relaparoscopy, may be necessary in the presence of hemodynamic

instability or rupture of the hematoma, particularly when associated with an

underlying hepatic tumor2,3,5,9.

Summary/Conclusion

ISH is an extremely rare but life-threatening

complication following LC. This case demonstrates the necessity of monitoring

patients who undergo LC and considering the possibility of ISH, although being

rare, in those who experience refractory postoperative hypotension. There is

still no universally accepted theory regarding the cause, treatment and

outcomes of this rare entity.

Consent

Written Informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of her case as a report and was documented in the

patient’s medical notes. A copy of the written informed consent would be

available for review by the editor-in-chief of the journal on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts

of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

References

2. Eltaib Saad LO. Giant

Intrahepatic Subcapsular Haematoma: A Rare Complication following Laparoscopic

Cholecystectomy-A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Reports in Surgery

2020.