Malignant Insulinoma: Case Report and Literature Review

Summary

Insulinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas

capable of secreting insulin. They are rare and the incidence varies according

to the center considered. Fasting hypoglycemia in a non-diabetic patient (blood

glucose below 55 mg/dl) is the most common clinical manifestation of insulinoma

and the presence of neuroglycopenic symptoms that may be preceded by autonomic

symptoms. The diagnosis of insulinoma requires inappropriately high levels of

insulin and C-peptide, associated with hypoglycemia. After the biochemical

diagnosis, the tumor must be located by imaging techniques such as ultrasound

and computed tomography of the abdomen. Malignant tumors have little or no

cellular pleomorphism, hyperchromasia or high mitotic activity, tend to have a

worse prognosis and the management of hypoglycemia, as well as the resolution

of associated metastases, is a challenge. The benefit of primary tumor

resection in patients with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors is also

controversial.

Keywords: Hypoglycemia; Insulinoma; Neuroendocrine tumors

Introduction

Insulinoma has an incidence of approximately 4 cases per million inhabitants per year (1-3) and is frequently benign, single, sporadic and less than 20 mm1-5. Between 2-7% present as part of a Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) syndrome and up to 6% may present liver or lymph node metastases (malignant insulinoma)1-5.In insulinoma, a median age at diagnosis of 56 ± 18 years has been described and no differences between genders have been observed6.Its usual clinical presentation consists of the so-called Whipple Triad (characterized by the presence of symptoms: tremor, sweating, tachycardia; low blood glucose levels and relief of these symptoms by ingesting carbohydrates)5.Hypoglycaemia is mainly due to reduced hepatic glucose production, rather than increased glucose utilization7.

There are neuroglycopenic symptoms such as: confusion, visual changes and unusual behaviour and then sympathetic-adrenal symptoms: palpitations, diaphoresis and tremors. In addition, there could be hyperphagia, which can determine weight gain in these patients.

Diagnosis of insulinoma requires the demonstration of excessively high plasma insulin concentrations during an episode of spontaneous or provoked hypoglycaemia.

Once

the laboratory diagnosis has been made, the location of the tumour is required

and transabdominal ultrasound and computed tomography are preferred. When the

tumour is not located by initial imaging studies, additional options include

other non-invasive or invasive tests such as endoscopic ultrasound (endoscopic

ultrasound). This is a highly sensitive and specific procedure for the

localization of pancreatic endocrine tumours8.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, on the other hand, is proposed for the detection

of insulinomas, when endoscopic ultrasound is negative9.

Other

non-invasive imaging tests include magnetic resonance imaging and

fluorine-18-L-dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography (18F-DOPA

PET) (10). Ga-68 gallium PET/CT (a somatostatin receptor-based imaging

modality) is an option when conventional imaging studies do not identify an

insulinoma. It is capable of identifying most of these tumours and can be

considered as a complementary imaging study when all imaging studies are

negative and when surgical treatment is planned11.

The

World Health Organization established a classification of malignant

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours based on a scheme of criteria

such as tumour size < 2 cm versus > 2 cm and presence of metastasis;

grade (mitotic rate, perineural and lymph vascular invasion, proliferative

index Ki-67)12.

Another

classification scheme estimates malignant potential using accurate prognostic

information by combining tumour size and metastases with simple classification

information based on necrosis and mitotic rate13.

Treatment

of sporadic insulinomas is surgical, but when it is more than one lesion, it is

debatable because it requires very extensive procedures with endocrine and

exocrine pancreatic functional loss.

The

liver and regional lymph nodes are the most common sites of metastatic disease.

In these cases, surgical treatment, hepatic artery embolization,

radiofrequency, cryoablation or even systemic therapy are considered14.

Medical

treatment to control hypoglycaemia is necessary in patients who are not subject

to surgery or in those who have unresectable metastatic disease or to control

recurrent hypoglycaemia while waiting for surgery14.

Diazoxide is used in the first line, but

octreotide or lanreotide because they are somatostatin analogues and as other

options verapamil or phenytoin can be used.

If

postoperative remission is achieved, the probability of recurrence of

insulinoma is low (<10%), but survival is worse in older patients and in

those with metastatic disease15.

Clinical

Case

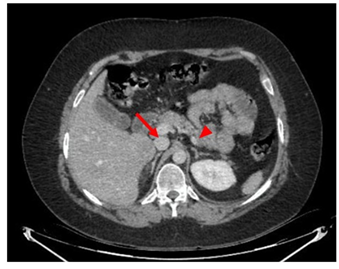

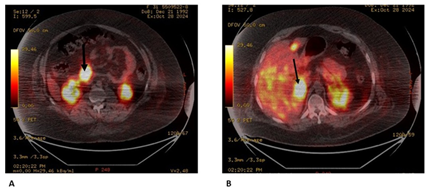

A 33-year-old man with a history of psychiatric pathology treated with risperidone since childhood. In the previous three years, he presented multiple episodes of symptomatic hypoglycaemia that required hospital admission and management with continuous infusion of glucose serum, with blood glucose values that reached 35 mg/dl, seizures and loss of consciousness, which require management in intensive care. During the evaluation, a computed tomography of the abdomen was requested, which showed 2 pancreatic lesions, one in the body of 28 mm and another in the uncinate process of 42 mm. Additionally, multiple focal lesions were found in the liver, the largest of which was 32 mm (Figure 1). Likewise, venous glycemia of 37 mg/dl, insulin of 137 (normal range 2 to 12 μU/mL) and increased C-peptide of 8.27 (normal range 1.1 to 4.4 ng/ml) were found, which allowed a diagnosis of malignant insulinoma with liver metastases. A PET-CT scan with 18F-NOTATOC confirmed that pancreatic and hepatic lesions expressed somatostatin receptors (Figure 2a and 2b).

Figure 1: Axial computed tomography scan. Insulinoma is observed on the right in the uncinate process (arrow) and on the left (arrowhead)

Figure

2:

PET with 18F-NOTA-OCT

A: insulinoma

uptake is observed (arrow);

B: uptake of

multiple liver metastases and the largest one (image on the right)

Since

the disease was in an advanced stage, surgical intervention was ruled out and

other treatments were chosen in parallel. In May 2022, two trans arterial

embolization’s were performed in which the lesion in the head of the pancreas

and a couple of liver lesions were eliminated, although the lesion in the body

of the pancreas and other hepatic lesions persisted. As pharmacological

treatment (May-June 2022), immediate-release octreotide (400 mcg c/8 hours) and

diazoxide (200 mcg c/8hs) were initiated.

Additionally,

a dose of lutetium was administered, with a good therapeutic response achieving

glycemia, between 100-200 mg/dl without the need for glucose serum and

significant reductions in insulinemia values: 12.8 μU/mL and C-peptide: 2.80

ng/ml. Under these conditions, he is discharged, with evolutionary control.

During follow-up, he received 3 additional doses of Lutetium: (August 2022,

November 2022 and January 2023). However, she did not maintain follow-up with

endocrinology and received diazoxide only for the first month, opting to

maintain only extended-release octreotide for 28 days. In October 2024 he was

admitted to hospital for episodes of symptomatic severe hypoglycaemia of up to

20 mg/dl. It was necessary to use a continuous infusion pump of 30% glucose

serum for stabilization. Given the persistence of hypoglycaemia, the use of

glucocorticoids was attempted to promote hepatic gluconeogenesis and reduce

hyperinsulinemia. However, this treatment was not effective and the infusion of

glucose serum was maintained. A new 18F-NOTE-OCT PET scan was performed, which

showed the same hyper uptake lesions in the pancreas and liver, but larger than

in the previous study.

In

addition, he presented intense bone pain that limited his ambulation, so a

pelvic MRI was requested that confirmed osteonecrosis of both femur heads.

Biochemical

analyses showed calcemia of 10.5 mg/dL (normal range of 8.3 - 10.3 mg/dL), PTH

of 243 pg/mL (normal range 15 - 65 pg/mL), with vitamin D < 3 ng/mL (normal

range 30-120 ng/mL), phosphate, azoemia and normal blood creatinine.

Urine/24-hour calciuria was also normal. With the approach of primary

hyperparathyroidism, a neck ultrasound was requested, which showed a

well-defined hypoechogenic solid nodular lesion, without vascularization of 9 x

7 x 7 mm, topographer in the left lower posterior thyroid sector. Parathyroid

scintigraphy could not be performed.

During

hospitalization, an attempt was made to embolize the lesions, but it was not

possible to locate the nutritious arteries of the tumours. Lutetium was

requested, but the tracer radio was not accessed. Despite the glucose serum and

diazoxide, the patient presented seizures that culminated in his death.

Discussion

The presence of

Whipple's triad, as in this case, supports the presence of pathological

hypoglycaemia. Adequate questioning and physical examination, with the

complementary laboratory, determine the aetiology of hypoglycaemia in a

non-diabetic patient. In people without underlying diseases, who do not take

drugs that cause hypoglycaemia like this patient, the most likely aetiologies

of hypoglycaemia are endogenous hyperinsulinism or factitious hypoglycaemia16.

The onset of

hypoglycaemic symptoms usually occurs when blood glucose levels drop below 55

mg/dL, although the specific threshold varies between individuals and over

time. The counterregulatory response (such as the release of glucagon and

epinephrine) may appear with glycaemic levels approximately 10 mg/dl higher,

before the onset of hypoglycaemic symptoms. In addition, glycaemic thresholds

for these counterregulatory responses may be higher in patients with insulinoma17.

Although fasting hypoglycaemia is the most

common presentation of insulinoma18,

postprandial hypoglycaemia may be a concurrent or even the only manifestation

of hypoglycaemia in some patients, although the proportion is low19.

Up to 20% of patients

with insulinoma receive a misdiagnosis of a neurological or psychiatric

disorder before the insulinoma is recognized20,21.

We are left with the

doubt in this case, treated for psychiatric pathology with episodes suggestive

of hypoglycaemia of three years of evolution, which were not previously studied

if they were not interpreted as part of his psychiatric illness of years of

evolution and therefore the diagnosis of hypoglycaemia is delayed.

There is a case series

report with insulinoma, which showed that approximately 77% presented autonomic

symptoms and 96% neuroglycopenic symptoms; ≥80% presented confusion or abnormal

behaviour, 50% lost consciousness or presented amnesia of the event and between

12 and 19% presented grand mal seizures22,23.

The presence of

recurrent neuroglycopenic symptoms, as in this case, warrants supervised

testing to detect insulin-mediated causes of hypoglycaemia22,23.

In the case of the

report, the patient had neuroglycopenic symptoms and a convulsive state of

great malice that requires admission to intensive care. And insulin and

C-peptide levels were inappropriately elevated for plasma glycemia, raising the

diagnosis of “hyperinsulinism hypoglycaemia” or hypoglycaemia with endogenous

hyperinsulinism. Once the biochemical diagnosis has been established, the

tumour causing insulin secretion must be located. Insulinomas can be single or

multiple, localized or metastatic.

Although most are

solitary tumours, approximately 10% of patients have multiple intrapancreatic

tumours14,24.

The vast majority

(≥90%) of insulinomas remain localized in the pancreas24,25.

Tumours are usually

small, with an average size of about 1.5 cm and can sometimes be difficult to

locate by preoperative imaging26.

In this case there were two pancreatic lesions but the size was just over 4 cm

the largest and that can speak of evolution time because he has been with

episodes of hypoglycaemia or tumour aggressiveness for three years due to a

potential for rapid growth.

The pathologic

appearance alone cannot determine whether a tumour is likely to be indolent and

confined to the pancreas, as opposed to aggressive and likely to metastasize.

Therefore, extension outside the pancreas is used as a marker of aggressive

clinical course and risk of future recurrence. A higher prevalence of MEN1 is

suggested among patients with multiple tumours (25%) and metastatic disease

(13%), compared to a prevalence of 7.6% in the general population (14). Others

report that up to 5-10% of insulinomas are associated with MEN-127, so it is essential to rule it out in

these patients. In our case, the presence of mild hypercalcemia and elevated

PTH suggests a possible diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism (PPH).

Although to confirm this, it is essential that vitamin D is in a range of

sufficiency, since its deficiency can raise PTH levels secondarily. But

hyperparathyroidism secondary to vitamin D deficiency usually does not cause an

increase in PTH well above 100 pg/ml, in this case it is much more. A finding

that reinforces the suspicion of PPH is the lesion described in the neck

ultrasound suggestive of parathyroid adenoma. In addition to osteonecrosis of

the femur, it could be a possible consequence of PPH28.

As stated above, the

ideal for the localization of the insulinoma is ultrasound and computed

tomography. In our case, the CT scan found the insulinoma and the PET scan was

added as a complementary study.

The treatment of choice

is surgery, which achieves cure in up to 90% of patients with benign

insulinomas4,5. In the case of

malignant insulinomas, surgery of the primary tumour increases survival between

12 and 28 months and allows better management of symptoms, although it is not

curative5.

Other therapeutic

strategies include invasive procedures such as chemical or radiofrequency

ablation or embolization of nutritive arteries, but there are also

pharmacological therapies for symptomatic control such as glucose serum,

diazoxide, somatostatin analogues, therapy with peptide receptor radionuclides

(lutetium) or chemotherapy4,5.

Medical treatment

includes fractionation of the diet, somatostatin analogues, diazoxide and

lutetium cone was raised in this case; but other drugs such as everolimus,

sunitinib could also be used when the previous ones did not work.

Somatostatin analogues

have been shown to not only improve symptoms and reduce tumour size in

well-differentiated tumours, but also stabilize the progression of liver

metastases in some cases.

In patients with

somatostatin receptor-positive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, such as in

this patient, if the disease is of low volume, initial treatment with a

long-acting somatostatin analogue such as octreotide and lanreotide is

suggested29.

In those with

symptomatic hepatic-predominantly low-volume disease, hepatic arterial

embolization, chemoembolization or radioembolization may be used.

In our case, the

patient had two pancreatic NETs and positive for somatostatin receptors

demonstrated with PET, but of high volume, so the initial treatment options

that can achieve a reduction in the disease burden include treatment with

radionuclides of peptide receptors with positive somatostatin receptors, plus

liver-directed therapy or capecitabine plus temozolomide that he did not

receive. Since they had a PET scan that showed radiotracer uptake, they may

benefit from treatment with these radiopharmaceuticals.

Treatment with

long-acting somatostatin analogues may retard tumour growth in patients with

locally advanced or well-differentiated somatostatin receptor-positive

pancreatic NETs and for that reason it was used in this case30.

In patients with

locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic pancreatic NETs that are positive

for somatostatin receptors, initial therapy with lutetium Lu-177 dotatate in

combination with octreotide or lanreotide improves tumour response compared to

high-dose octreotide31. For small

(< 3 cm) neuroendocrine liver metastases, radiofrequency ablation,

cryoablation, microwave ablation is most often used as an adjunct to surgical

resection. Another suitable option for initial treatment in these advanced

stages is liver-directed therapy, such as: hepatic arterial embolization,

chemoembolization or radioembolization. However, the survival benefit of this

treatment is less clear. In this case, it was performed, but then tried again

without success, when the disease progressed (32).

Hepatic arterial

embolization is frequently applied as a palliative technique in patients with a

metastatic neuroendocrine tumour of hepatic predominance who are not candidates

for surgical resection, which was the case in our case. It is based on the principle

that liver tumours obtain most of their blood supply from the hepatic artery,

while healthy hepatocytes obtain it from the portal vein32.

In this patient, the

expression of somatostatin receptors in the pancreas and in liver metastases

allowed the use of lutetium, achieving a favourable initial response with

reduction of hypoglycaemia and tumour stabilization. However, over time, the

disease progressed, suggesting possible resistance to treatment. Like trans

arterial embolization that was used, but in a second attempt it was not

achieved.

When the patient began

to present with recurrent hypoglycaemia despite the administration of

subcutaneous octreotide every 8 hours, the possibility of a paradoxical

aggravation of hypoglycaemia due to inhibition of the secretion of

counterregulatory hormones was raised. However, this hypothesis was discarded,

as hypoglycaemia persisted even after treatment was discontinued.

Conclusions

Insulinoma

is the most common functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour that causes

hyper insulinemic hypoglycaemia. Early diagnosis and intervention, particularly

in patients with a history of neurological or psychiatric problems,

postprandial symptoms or rapid improvement in symptoms after treatment, can

lead to significantly better outcomes18.

The therapeutic management of malignant insulinomas is complex and requires a

multidisciplinary approach. Surgery is the treatment of choice in respectables

cases; however, in advanced stages, as in this case, palliative strategies are

used with the main objective of controlling symptoms and improving the

patient's quality of life.

References

14. Vella

A, Nathan DM. Insulinoma. En UpToDate, Rubinow K (Ed), Wolters Kluwer 2025.

28. Ang Chan J, Kulke M, Clancy T et al. Metastatic

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Local options to control tumor

growth and symptoms of hormone hypersecretion. En UpToDate, Sonali M S (Ed),

Wolters Kluwer 2025.