Multimodal Musculoskeletal Treatment in Refractory Chronic Headache: A Case Report

Abstract

Patients with chronic headaches frequently experience disabling

symptoms that heavily impact their quality of life and ability to perform

activities of daily living. Current standard treatment focuses on pharmacologic

interventions and includes abortive therapies such as analgesics and

migraine-targeting therapies. We report a case of a 66-year-old female with a

12-month history of a persistent, refractory secondary headache characterized

by cervicogenic and occipital neuralgia features, unresponsive to multiple

pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions. After little progress was

made with her previous treatment plan of analgesics, Rimegepant (Nurtec),

physical therapy and dry needling, the patient was offered a multimodal

musculoskeletal approach, including acupuncture, osteopathic manual therapy

(OMT) and home exercise recommendations by a single physician provider. These

therapies have been shown to provide relief in patients suffering from chronic

pain. Following this multimodal approach, the patient reported significant

symptom relief in their headache frequency and intensity, allowing her to have

less reliance on medication, while also significantly improving her sleep

quality. This case demonstrates a potential avenue for further research to hopefully

develop new minimally invasive treatments of chronic headaches that can improve

a patient’s quality of life.

Keywords: Chronic headache; Multimodal musculoskeletal treatment;

Alternative medicine

Introduction

Chronic headaches are characterized by recurrent headaches occurring on

at least 15 days per month for a duration of three months or longer1. They

represent a debilitating neurological disorder that places a considerable

strain on the individual, ultimately diminishing their quality of life (QOL).

Compared with episodic headaches, those who suffer from chronic headaches

experience greater impairment in Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), higher

rates of missed activities of daily living and frequent psychiatric

comorbidities such as anxiety and/or depression1. Acute therapies include

analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or

migraine-targeting therapeutics such as triptans or ergot derivatives.

Preventive treatments remain limited, with evidence supporting only a few

agents such as onabotulinumtoxinA (BoNT-A), topiramate and CGRP-targeted

monoclonal antibodies2. Despite the variety of pharmacological options,

frequent use is discouraged due to the risk of medication adverse effects or

precipitation of medication overuse headaches (MOH). This underscores the need

for non-pharmacologic adjuncts, such as osteopathic manipulation treatment

(OMT) and acupuncture.

Osteopathic manual therapy (OMT) is a form of manual therapy taught as

part of the curriculum in American Osteopathic Medical Schools and

international Osteopathy programs that emphasize the body’s natural capacity

for self-healing through the interplay of structure and function. In several

studies, OMT has been shown to effectively treat headaches by a few mechanisms,

including releasing restrictions in fascia, joints and muscles, thereby

promoting a return to physiologic homeostasis3. In parallel, studies suggest

that acupuncture is effective for a variety of chronic conditions, including

headaches, as it has few adverse effects while promoting analgesia, releasing

endogenous endorphins and improving psychological stability4. Although both OMT

and acupuncture show promise in the broader management of acute and chronic

pain as individual treatments, their roles when applied together in a cohesive

treatment model in headache treatment remain unexplored3-5. This case report

aims to describe a patient with refractory, chronic headache whose symptoms and

QOL improved following a multimodal musculoskeletal treatment approach that

incorporated OMT, acupuncture and additional therapeutic modalities.

Case Report

A 66-year-old female patient, with a past medical history significant

for squamous cell carcinoma of the scalp vertex excised in February 2024,

sought care for her persistent headaches that began in May 2024. She described

the pain as an aching sensation that originated at the base of her left occiput

and radiated anteriorly across the scalp. Her headaches occurred daily, lasted

multiple hours, but were without photophobia, phonophobia or aura. Given the

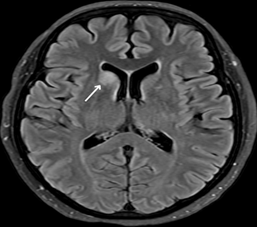

concern of new-onset headache, an MRI was performed, which revealed a 1-cm

right caudal mass (Figure 1).

Figure

1:

Axial FLAIR MRI of the brain reveals a 1-cm hyperintense lesion in the right

caudal region (arrow)

She

was subsequently evaluated by multiple physicians, in which there were

differences in the leading differential diagnosis, including glioma, venous

angioma or nonspecific white matter disease. Neurosurgical evaluation

recommended non-surgical management and serial MRI monitoring, which revealed

unchanging size and appearance of the intracranial lesion. Despite radiographic

stability, her headaches worsened in duration and intensity, which

substantially impaired her QOL. The patient’s headaches were most likely

multifactorial in origin, with plausible contributors being the intracranial

lesion, prior vertex carcinoma excision, cervical and periscapular

musculoskeletal dysfunction, postural abnormalities and/or age-related

degenerative changes.

Initial

management, including physical therapy, dry needling, Rimegepant (Nurtec) and

NSAIDs, provided only a transient benefit. After approximately 12 months of

persistent, refractory symptoms, the patient presented to our family medicine

and lifestyle medicine clinic in May 2025 for further evaluation. On physical

examination, there were no focal neurological deficits; however,

musculoskeletal assessment revealed upper trapezius hypertonicity, weakness of

the scapular depressors and tenderness to palpation at the occipital base.

Based on her symptomatology and physical examination findings, her headaches

demonstrated features consistent with chronic cervicogenic headache and

occipital neuralgia.

A

multimodal musculoskeletal approach was used for treatment, which incorporated

acupuncture, OMT and a home exercise program. The treatment began with

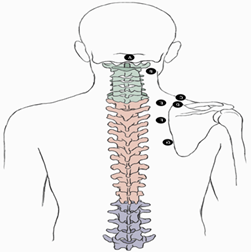

acupuncture using posterior cervical and upper thoracic acupoints that

corresponded with the patient’s pain distribution (Figure 2) with the

goal of modulating nociceptive input and improving regional muscle tension.

Figure

2:

Acupoints used in adjunctive therapy for headaches in the reported case

A:

GV16; B: BL10; C: GB21; D: TW15; E: BL11; F: BL13; G: BL38. Although

illustrated unilaterally, all points were applied bilaterally during treatment

Following

acupuncture, osteopathic manipulative techniques (OMT) were utilized to

optimize musculoskeletal function by addressing relevant somatic dysfunction.

Myofascial release (MFR) and then muscle energy (ME) were performed to target

trapezius hypertonicity and scapular depressor weakness. The treatment sequence

was then concluded with a high-amplitude, low-velocity (HVLA) thrust to the

thoracic spine to improve any residual thoracic restriction, restoring thoracic

mobility. Due to exhibited weakness in scapular depression, the patient was

given a daily exercise plan based on reciprocal inhibition principles to help

activate her scapular depressors, thus reducing muscular tone in upper-cross

muscles that may contribute to headaches6.

These therapies were done at her weekly appointments over the next month, with

progressive refinement based on symptomology. During her treatments, the

patient reported no adverse effects from therapy, including worsening headache

symptoms, new neurologic complaints, dizziness, syncope or functional

impairment. She was eventually seen every three weeks and by six months of

treatment, she reported substantial and sustained clinical improvement in

headache frequency and intensity, which allowed her to have less reliance on

medication and improve her sleep quality (Table 1).

Table

1:

Comparative assessment of patient’s symptoms before and after treatments at 6

month follow up

|

|

Before

treatment |

After

6 months of treatment |

|

Headache

Frequency |

Daily |

1-2

per month |

|

Headache

Duration |

At

least 4 hours |

Maximum

1-2 hours long |

|

Awakened

from sleep due to pain |

1

time/week |

No

longer occurring |

|

Severe

headache limiting daily function |

2

episodes/week |

No

longer occurring |

|

NSAID

dependency |

Four

Ibuprofen tablets daily |

Required

medication twice (two ibuprofen each) in the last six months |

Discussion

Headaches

represent one of the most common reasons for medical visits, both in emergency

and primary care settings3. The

pathophysiologic mechanism of chronic headaches is often multifactorial,

including a combination of psychological stress, lifestyle triggers,

musculoskeletal dysfunction and alterations in the central and peripheral pain

pathways. As seen in this case, conventional therapies do not always provide

sustained symptomatic relief and improvement in QOL. Since prior attempts at

management provided only transient benefit, it was clear that a broader

therapeutic approach was necessary and that no single modality was sufficient.

With that, a multimodal musculoskeletal approach was used to engage in multiple

therapeutic pathways, including biomechanical, myofascial and neuromodulator

mechanisms9. In this patient,

diagnostic evaluation could not attribute the symptoms to a single aetiology;

however, physical examination did reveal cervical and periscapular dysfunction,

which are known to contribute to cervicogenic headaches. In patients with

headache phenotypes characterized by occipital neuralgia and cervicogenic

features, such as this patient, targeted manual therapies may help alleviate

symptoms by reducing cervical and suboccipital muscle tension and improving

biomechanical function7.

Chronic

headaches and OMT

It

is important to acknowledge that the brain itself does not have pain receptors

and so the headache pain is often referred from the surrounding head, neck and

upper thoracic structures. Specifically, the muscles of the suboccipital

triangle, rectus capitis posterior major and obliquus capitis superior and

inferior can undergo hypertrophy and/or asymmetry, resulting in possible

occipital nerve compression. Dysfunctions in these musculoskeletal structures

can perpetuate symptoms, which underscores the potential value of osteopathic

manipulation in targeting these dysfunctions. In many cases, dysfunctions in

the body can manifest as observable TART changes, also known as viscero-somatic

dysfunctions. TART is an osteopathic acronym that refers to tissue texture

changes, asymmetry, restricted motion and tenderness8. It is through these palpable changes, as

well as other physical examination findings, that a somatic dysfunction can be

diagnosed. OMT is not only used to diagnose somatic dysfunctions, but can also

provide treatment by alleviating symptoms and subsequently reducing pain3. Generally, treatments can be categorized

as either active or passive (based on the patient’s involvement) and direct or

indirect (based on the direction of treatment being away from or towards the

restriction)8. The most common

osteopathic techniques in the cervical spine are myofascial release and muscle

energy8.

In

terms of the utilized treatment for this patient, myofascial release was

applied in both a direct and indirect technique, with passive movements

following the fascia in all directions of ease. This is intended to release the

tension in the fascia and muscle fibres of the hypertonic upper-cross and

cervical muscles. Both post-isometric relaxation and reciprocal inhibition of

muscle energy were utilized in the patient’s treatment plan. Muscle energy with

post-isometric relaxation involved contracting the upper trapezius and

rhomboids against an isometric force by the physician, followed by a few

seconds of relaxation, which allowed for lengthening of the hypertonic muscles

and increasing range of motion9.

The treatment ended with HVLA, which was an applied, rapid force directed at

the cervical facet joints, engaging the restrictive barrier and ultimately

releasing the restriction9. Beyond

in-office manual intervention, multimodal care also focuses on addressing

psychosocial and lifestyle factors, including postural habits5. Postural habits, including forward-head

posture and chronically elevated scapular positioning, can lead to inhibition

and poor neuromuscular control of key scapular stabilizers. With weakened

scapular stabilizers, there is compensatory overuse of upper-cross and cervical

muscles and subsequently increased tension in the cervicothoracic junction10. Reducing hypertonic muscles like the

rhomboids helps restore proper scapular motion and positioning, thereby

reducing the mechanical stress that contributes to headache triggers. As seen

in this case, this was ensured by providing the patient with a home exercise

plan grounded in the principles of reciprocal inhibition and emphasizing

posterior scapular chain activation6.

The patient was instructed to perform an activation drill emphasizing

controlled scapular retraction followed by scapular depression to

preferentially activate antagonist muscles, like the lower trapezius and

pectoralis minor. Activation of the stretch reflex of the muscle spindle fibres

of those muscles caused the agonist muscles, such as the upper trapezius and

rhomboids, to reflexively relax9.

Additionally, this activation drill simultaneously retrained scapular control

away from a chronically elevated posture towards a more dynamic motion.

Researchers

hypothesize that OMT rebalances the autonomic nervous system, reduces

pro-inflammatory substances, activates Golgi tendon organs and inhibits

hypertonic muscles, all of which are associated with headaches3,7. Multiple systematic reviews and

clinical trials have demonstrated that OMT significantly reduces pain intensity

and improves function in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, such as

chronic back pain. Specifically in headaches, OMT has been associated with

reductions in headache frequency, intensity and duration, as well as

improvement in functional outcomes and QOL8.

Not only do osteopathic techniques reduce pain, but studies have also indicated

that combining multiple osteopathic approaches yields greater relief and

headache reduction7.

OMT

has demonstrated a favourable safety profile, with reported adverse effects of

discomfort, light-headedness and/or stiffness. Most of these adverse effects

were reported within four hours of treatment and almost 75% had resolved

symptoms within 24 hours11. In

addition to safety, evidence suggests potential downstream benefits of manual

therapies in reducing medication reliance. A large retrospective cohort study

of adults with tension-type headache found that patients receiving spinal

manipulative therapy had a significantly lower risk of butalbital prescription

and a reduced risk of developing medication overuse headache over two years of

follow-up compared with matched controls12.

Although current evidence supports OMT as a low-risk modality, additional

studies with larger sample sizes are needed to fully characterize the safety

and long-term outcomes of OMT, particularly when multiple techniques are

applied in a single session11,12.

Chronic

headaches and acupuncture

Recent

studies, in parallel with Western medicine, have shown that acupuncture may

stimulate the release of endogenous opioids, serotonin and norepinephrine that

have downstream effects on nociceptors, inflammatory cytokines and

physiological pain perception13.

However, the mechanism of acupuncture is not completely known13. Chronic headaches involve dysfunctional

pain processing and central sensitization, including altered activity within

brainstem pain modulatory circuits and trigeminovascular pathways2. These neurological pathways may be

influenced by the neuromodulator effects proposed in acupuncture therapy,

providing a plausible contribution for symptom modulation in refractory

headaches. Acupuncture has been studied explicitly in patients with chronic

headaches, in which a Cochrane review showed that patients who received verum

acupuncture had at least a 50% reduction in headache frequency when compared

with usual care or sham acupuncture13.

Additionally, another study showed that acupuncture improved the general state

of health, mental health and functional capacity domains4. Ultimately, the authors concluded that

acupuncture reduced pain and frequency of crises, minimized dependence on

analgesics, improved quality of life and recommended it as an adjunctive

therapy for those suffering from chronic headaches4,13.

Regarding

safety, both acupuncture and OMT are generally regarded as low-risk treatment

options. Acupuncture is generally well tolerated, with minimal adverse effects,

such as fatigue, local pain or micro bleeding14.

With any procedure that involves needle introduction, there is a risk of

bleeding, infection, nerve injury or trauma, such as a pneumothorax14. Overall, complications with acupuncture

are infrequent and result in far fewer adverse effects relative to

pharmacological therapies14.

However, additional clinical studies are needed to further assess the safety of

acupuncture in the treatment of headache disorders13,14.

In

addition to its safety profile, it is relatively cost-effective compared to

standard care. For example, economic analyses from the United Kingdom estimated

a cost of $12,080 per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gained with acupuncture

for patients suffering from chronic headache disorders, which falls well below

commonly accepted cost-effectiveness thresholds13.

By comparison, long-term pharmacologic management may offer limited sustained

benefit, is associated with potential adverse effects and may be associated

with higher long-term cost depending on medication class and duration of use5. Overall, available evidence supports

acupuncture as a safe and cost-effective therapeutic option for the management

of chronic headache disorders.

Multimodal

musculoskeletal model

Acupuncture

and OMT have gained increasing recognition for their effectiveness in disorders

resulting in chronic pain3,13.

Not only do both independently serve as effective treatments for pain, but when

applied as a multimodal musculoskeletal treatment model, they can produce

synergistic and lasting benefits5.

Although individual therapies have been shown to reduce headache burden,

studies have shown that a multimodal musculoskeletal treatment approach

optimizes pain management and rehabilitation5.

Pain is inherently complex and multifactorial. It is shaped by biological,

psychological and lifestyle factors. Therefore, a more holistic approach is

necessary to address all dimensions associated with pain management.

Integrating multiple therapeutic modalities allows healthcare providers to

address the physical, psychological and functional symptoms by leveraging the

strengths of each modality. Unfortunately, current musculoskeletal care is

often fragmented in practice. Patients are being referred to multiple providers

for the management of a single clinical issue, which delays care and reduces

follow-through. This delay causes many to rely solely on pharmacological

measures5. This fragmentation is

linked to prolonged pain, decreased function and poorer outcomes. However, a

coordinated, multimodal approach can improve the level of care integration,

promoting continuity of care. Providers can deliver this coordinated care

either through a single practitioner skilled in multiple therapies or within a

clinic where all services are accessible in the same facility in conjunction

with one another5. This approach

is particularly valuable for chronic headaches, many of which either arise from

or are exacerbated by musculoskeletal dysfunction. Even in secondary headaches

not caused by musculoskeletal dysfunctions, postural strain and muscle tension

can still develop, further worsening symptoms. Addressing these musculoskeletal

dysfunctions in an integrated way can help break the pain cycle and improve

overall outcomes. In this case, the precise cause of the patient’s headaches

was uncertain. Despite this uncertainty, she experienced significant symptom

relief and improved function. This case highlights the value of multimodal care

in providing meaningful benefits for patients with chronic headaches, even when

the underlying pathology is unclear.

Limitations

Certain

limitations should be considered when interpreting this case. After initial

imaging revealed a 1-cm caudal mass, serial MRIs were performed. However, the

mass remained unchanged in terms of size and appearance and subsequently was

unable to be used to monitor the patient’s symptoms and/or response to

treatment. Instead, treatment response was primarily measured using symptom

outcomes reported by the patient, including headache frequency, intensity,

duration, sleep disruption, functional limitation and medication use. Given the

potential for bias, future studies should include the use of a standardized,

objective metric separate from subjective data. As this report involved a

single individual, future studies should include larger sample sizes and control

groups to enhance generalizability and strengthen the evidence. In this

patient, there were multiple contributors that could have led to her headache,

such as the stable intracranial lesion, post-surgical changes, musculoskeletal

dysfunction, postural strain and age-related degenerative changes. Therefore,

the observed improvement in symptoms cannot be attributed to the treatment of a

single headache subtype. Additionally, further investigation is warranted to

determine whether combined multimodal therapies is superior in terms of

clinical benefit in comparison to individual interventions alone. All of these

future studies will help further establish the efficacy of both OMT and

acupuncture as individual interventions in chronic headaches, as well as when

used in combination.

Conclusion

Patients

with persistent, chronic headaches frequently experience debilitating physical,

psychological and functional impairment, which can significantly impact a

patient's quality of life. In this report, a coordinated multimodal

musculoskeletal treatment approach was used in the management of a patient

suffering from chronic headaches resistant to conventional care. This treatment

plan integrated OMT, acupuncture and home exercises, all rendered by a single

physician provider. Following this intervention, the patient reported reduced

headache frequency and intensity, improved sleep quality, decreased reliance on

analgesic medications and enhanced ability to perform activities of daily

living. While these findings are limited by the descriptive nature of a single

case, this report supports consideration of a coordinated, patient-centred,

multimodal approach for chronic headaches that are refractory to conventional

management. The observed clinical improvement reflects that the combination of

multiple therapeutic modalities may have a synergistic effect. It has been in

both the authors’ clinical experience in this current case, as well as other

cases, that the combination of multiple interventions at once provided improved

clinical outcomes. Due to the significant global impact of headaches, further

investigation, using larger cohorts and standardized outcome scales, is

warranted to determine whether multimodal musculoskeletal interventions are

clinically superior to individual therapies.

Acknowledgements

No

additional acknowledgements to declare.

Conflicts

of interests

No

conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

No

funding to declare.

Ethical

Approval

Consent

of all participants was obtained.

References

1. Ahmed F, Parthasarathy R, Khalil M. Chronic daily headaches. Ann

Indian Acad Neurol 2012;15:40-50.

2. Mungoven TJ, Henderson

LA, Meylakh N. Chronic Migraine Pathophysiology and Treatment: A Review of

Current Perspectives. Frontiers in Pain Res 2021;2.

3. Chin J, Qiu W, Lomiguen CM, Volokitin M.

Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment in Tension Headaches. Cureus 2020;12(12)

4. Mayrink WC, Garcia JBS, Dos

Santos AM, Nunes JKVRS, Mendonça THN. Effectiveness of Acupuncture as Auxiliary

Treatment for Chronic Headache. J Acupuncture Meridian Studies

2018;11(5):296-302.

5. Behringer C, Nagib N,

Nagib N. Introduction to multimodal musculoskeletal treatment models: a

viewpoint. Discover Applied Sciences 2025;7(8).

6. Owensboro Health.

Posterior Chain Activation 2. YouTube 2026.

7. Jara Silva CE, Joseph AM,

Khatib M, et al. Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment and the Management of

Headaches: A Scoping Review. Cureus 2022;14(8).

8. Lumley H, Omonullaeva N,

Dainty P, Paquette J, Stensland J, Reindel K. Current Use and Effects of

Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment (OMT) in the Military: A Scoping Review.

Cureus 2025.

9. Roberts A, Harris K,

Outen B, et al. Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: A Brief Review of the

Hands-On Treatment Approaches and Their Therapeutic Uses. Medicines.

2022;9(5):33.

10. Im B, Kim Y, Chung Y, Hwang

S. Effects of scapular stabilization exercise on neck posture and muscle

activation in individuals with neck pain and forward head posture. J Physical

Therapy Sci 2015;28(3):951-955.

11. Degenhardt BF, Johnson JC,

Brooks WJ, Norman L. Characterizing Adverse Events Reported Immediately After

Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment. J American Osteopathic Association

2018;118(3):141.

12. Trager RJ, Williamson TJ,

Makineni PS, Morris LH. Association Between Spinal Manipulation, Butalbital

Prescription and Medication Overuse Headache in Adults with Tension‐Type

Headache: Retrospective Cohort Study. Health Science Reports 2024;7(12).

13. Kelly RB, Willis J.

Acupuncture for Pain. American Family Physician 2019;100(2):89-96.

14. Van Hal M, Dydyk AM, Green

MS. Acupuncture. PubMed 2023.