Parathyroid Carcinoma Presenting with Severe Primary Hyperparathyroidism and Osteolytic Skeletal Lesions: A Case Report

Abstract

Parathyroid carcinoma is an exceptionally rare

malignancy typically presenting with severe primary hyperparathyroidism.

Diagnosis is often difficult and relies mainly on histopathological evaluation.

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with chronic

right hip pain and anxiety disorder, who presented with progressive general

deterioration. Clinical examination revealed a firm, painless, anterior

left-lateral basocervical mass measuring approximately 6 cm. Laboratory

investigations showed marked hypercalcemia (144 mg/L) and severe

hyperparathyroidism with a parathyroid hormone (PTH) level of 1,737 pg/mL (39

times normal). Imaging studies demonstrated a large heterogeneous mass adjacent

to the lower pole of the left thyroid lobe, associated with multiple osteolytic

skeletal lesions.

A giant parathyroid adenoma was suspected and surgical

excision was performed after preoperative correction of hypercalcemia. The mass

extended into the retrosternal space without invasion of adjacent structures.

Intraoperative histology suggested adenoma or hyperplasia. Postoperatively,

calcium and PTH levels normalized. However, definitive histopathological

analysis confirmed parathyroid carcinoma, showing capsular invasion and

vascular emboli.

At the six-month follow-up, the patient showed

significant improvement in bone pain, with no evidence of recurrence and normal

calcium levels. This case highlights the diagnostic difficulty of parathyroid

carcinoma and underscores the need for long-term surveillance due to the risks

of recurrence and metastasis.

Keywords: Parathyroid; Neoplasms; Carcinoma;

Hyperparathyroidism; Primary; Hypercalcemia; Parathyroidectomy

Introduction

Parathyroid

carcinoma (PC) is an exceptionally rare endocrine malignancy, accounting for

fewer than 1% of all cases of primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT)1. The condition was first documented in

1904 by the Swiss surgeon de Quervain2

in a patient presenting with a non-functioning parathyroid lesion. Since this

initial description, the global literature has progressively expanded our

understanding of this uncommon neoplasm.

In

this article, we describe a case of parathyroid carcinoma in a patient with

persistent pHPT, reported in accordance with the SCARE criteria3 and provide a concise review of the

relevant literature.

Presentation of Case

A

52-year-old man with a history of right hip pain and anxiety disorder for the

past three years presented with progressive deterioration of his general

condition. Physical examination revealed a firm, painless, anterior

left-lateral Baso cervical mass, mobile on swallowing, measuring approximately

6 cm in its greatest dimension, with a non-palpable inferior border (Figure

1). No cervical lymphadenopathy was detected and vocal cord mobility was

preserved.

Figure

1: Physical examination revealed anterior left-lateral Baso cervical mass,

mobile on swallowing, measuring approximately 6 cm in its greatest dimension,

with a non-palpable inferior border

Laboratory

investigations demonstrated marked hypercalcemia (144 mg/L) and severe

hyperparathyroidism, with an extremely elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) level

of 1,737 pg/Ml-approximately 39 times the upper limit of normal. Standard

skeletal radiographs revealed diffuse bone demineralization, predominantly

affecting the iliac bones, femoral necks and the right femoral diaphysis.

Cervical

ultrasonography identified a heterogeneous, hypoechoic and hypervascular mass

located adjacent to the lower pole of the left thyroid lobe, measuring 62 × 53

× 42 mm. Cervico-thoracic computed tomography (CT) confirmed a well-defined,

solid-cystic oval lesion beneath the left thyroid lobe, with smooth margins, measuring

54 × 45 mm and extending 63 mm in height. The mass showed close anatomical

relations with the left common carotid artery, situated anterior to it.

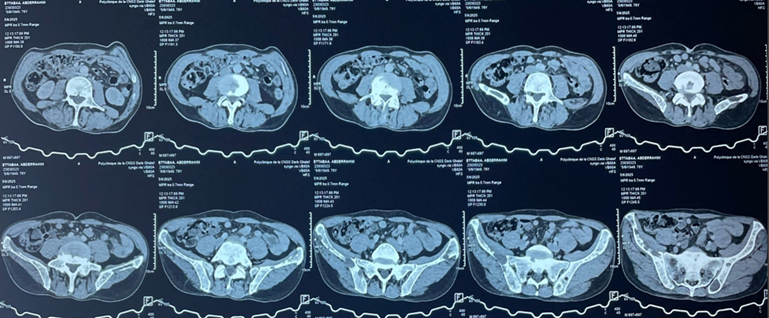

Additionally, multiple costal and vertebral osteolytic lesions were noted (Figure

2). Abdominopelvic CT revealed multiple osteolytic lesions involving the

spine and pelvis.

Figure

2: Axial abdominopelvic CT scan showing osteolytic bone lesions involving

the spine and the pelvis

Based

on these findings, a parathyroid adenoma was suspected and surgical excision

was planned. Preoperative management included intravenous rehydration with

isotonic saline and administration of bisphosphonates to correct the

hypercalcemia.

Intraoperatively,

the mass was found to be plunging into the retrosternal space, with no evidence

of infiltration or continuity with the lower pole of the left thyroid lobe,

which appeared macroscopically normal. A left inferior parathyroidectomy was

performed and the excised specimen was sent for intraoperative

histopathological examination, which suggested either an adenoma or parathyroid

hyperplasia without features of malignancy.

The

immediate postoperative course was uneventful. Biochemical assays on

postoperative day 1 demonstrated normalization of serum calcium (103 mmol/L)

and PTH levels (44 pg/mL).

Definitive

histopathological analysis established the diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma,

characterized by an encapsulated malignant proliferation composed of

parathyroid cells arranged in diffuse and nodular patterns, separated by

fibrous septa. The tumor cells were monomorphic, with abundant cytoplasm and

mildly atypical round nuclei. Mitotic activity was moderate (three mitoses per

ten high-power fields). Areas of capsular invasion and vascular tumor emboli

were also identified.

At

the six-month follow-up, the patient showed significant improvement in bone

pain, with no clinical or ultrasonographic evidence of local recurrence.

Laboratory findings confirmed normalization of serum calcium levels.

Discussion

Parathyroid

carcinoma (PC) is an extremely rare endocrine malignancy, representing less

than 0.005% of all cancers and accounting for approximately 0.5-4% of primary

hyperparathyroidism cases, with significant geographical variation reaching up

to 5% in Japan4,5. In Western

countries, PC usually accounts for less than 1% of pHPT cases6. Its incidence is estimated at 4-6 cases

per 10 million inhabitants per year and a large American series reported 286

cases over 10 years7,8. Because

of its rarity and lack of specific clinical and biological signs, PC is

frequently misdiagnosed as benign primary hyperparathyroidism and is often

diagnosed only postoperatively4,7,9,1.

The

etiology of PC remains poorly understood, although several environmental and

genetic factors have been implicated10,7,9.

Neck irradiation, particularly at a young age, increases the risk of

parathyroid neoplasia5,6.

Chromosomal abnormalities-including 1p, 4q, 13q losses and 1q, 9q, 16p, Xq

gains-have been reported11 and

cyclin D1 overexpression is found in most tumors12.

Parathyroid carcinoma also shows a strong association with

hyperparathyroidism–jaw tumor syndrome13.

Additional genetic abnormalities, such as RB, p53, BRCA2 and PRAD1 mutations,

have been described13.

Most

PCs are functioning tumors causing severe hypercalcemia, presenting with

fatigue, weakness, weight loss, anorexia, psychiatric symptoms,

gastrointestinal complaints, nephrolithiasis and bone lesions including brown

tumors10,14,15. Renal and

skeletal involvement is common at presentation16.

Dysphonia and dysphagia, resulting from recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion, are

highly suggestive of malignancy10.

Marked hypercalcemia-often above 3.5 mmol/L-is frequently observed11,17. Non-functioning carcinomas are

extremely rare and typically present with advanced local disease7,15,18.

Imaging

plays a key role in the evaluation of PC. Cervical ultrasound may show

lobulated hypoechoic lesions with irregular margins, intra-lesional

calcifications or infiltration of adjacent tissues-features suggestive of

malignancy10,15. Negative

predictive features include a thick capsule, ovoid shape or absence of

intratumoral vascularity10.

Ultrasound sensitivity ranges from 50% to 90%15.

Tc-99m sestamibi scintigraphy is useful for localization but cannot distinguish

adenoma from carcinoma; however, it may detect lymph-node or distant metastases15,19. CT and MRI offer better visualization

of soft tissue invasion and nodal involvement14,20.

FDG-PET may show uptake in brown tumors, which can mimic metastasis21. Fine-needle aspiration cytology is not

recommended due to false negatives and risk of capsular rupture22,23.

Intraoperatively,

PC typically appears as a firm, lobulated mass with a dense gray-white fibrous

capsule adherent to surrounding tissues, making dissection difficult17,24. Tumors are usually large (>3 cm)

and may involve adjacent structures25.

Histopathological diagnosis is difficult. Classic criteria include trabecular

architecture, fibrous bands, mitotic activity and capsular or vascular invasion7,1,26, but these features are not specific

and may also occur in benign lesions27.

Surgery

is the mainstay treatment for PC. Recommended management includes en bloc

resection of the tumor with ipsilateral thyroid lobectomy and excision of

involved lymph nodes14,15,28.

Complete excision provides the best chance of cure, while incomplete resection

is associated with recurrence7,14,15,24.

Avoiding capsular rupture is essential to prevent tumor seeding10. Lateral lymph-node dissection is

recommended only when nodal metastases are present28,29.

Although PC is traditionally considered radioresistant, radiotherapy may

improve local control in selected cases17,20.

Chemotherapy has not shown proven benefit7,10.

Recurrence

is frequent, occurring in 25% to 60% of cases within the first 2-5 years7,30. Late recurrences, sometimes beyond 20

years, have been reported, requiring prolonged follow-up7. Recurrence often presents with rising

serum calcium and PTH levels and may involve local, regional or distant

metastases31. Follow-up includes

physical examination and serial monitoring of calcium and PTH13. Management of hypercalcemia may require

loop diuretics, dialysis or bisphosphonates10,14.

References

1. Shane E. Parathyroid carcinoma. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 2001;86(2):485-493.

2. De

Quevain F. Malignant aberrant parathyroid. Dtsch Z Fuer Chir 1904;100:334-352.

5. Boudiaf

DE, Bouache MA, Kourtiche AS, Ouahioune W. Le carcinome parathyroïdien:

l’énigme diagnostique. Ann Endocrinol 2015;76(4):517-518.

14. Givi

B, Shah JP. Parathyroid Carcinoma. Clinical Oncology 2010;22:498-507.

15. Akoubkova

S, Vokurka J, Cap J, Ryska A. Parathyroid carcinoma: clinical presentation and

treatment. International Congress Series 2003;1240:991-995.

16. Koea

JB, Shaw JHF. Parathyroid cancer: biology and management. Surg Oncol 1999;8:155-165.

17. Trésallet

C, Royer B, Menegaux F. Cancer parathyroïdien. EMC Endocrinologie-Nutrition

2008.

26. Schantz

Z, Castleman B. Parathyroid carcinoma: a study of 70 cases. Cancer

1973;31(3):600-605.

28. Kassahun

WT, Jonas S. Focus on parathyroid carcinoma. Int J Surg 2011;9:13-19.

31. Kebebew E. Parathyroid carcinoma. Curr Treat

Options Oncol 2001;2:347-354.