The Ancient Art and Burial Practices in the Service of Mental Health (Images of the Soul in Ancient Egyptian Culture)

Abstract

The article raises the question of what constituted

images of the human soul in Ancient Egypt. To answer it, the author considers,

on the one hand, the image of man in the first two cultures (Archaic and the

culture of the Ancient Kingdoms) and on the other hand, the understanding of

art at that time. Four interpretations of the soul in Ancient Egypt are

analyzed (the ordinary one during life and four after death - “Ba”, “Ka”, “shadow”

and “Akh”). It is shown that from a theoretical point of view (in cultural

studies and semiotics), these interpretations can be understood as

objectifications of schemes created to resolve problematic situations in

certain anthropopractices, some of which we would today classify as practical

psychology. A reconstruction of these problematic situations and

anthropopractices is proposed. It is concluded that man and art were understood

in the Ancient world completely differently than in the Modern era and that

ancient art helped man cope with his problems, including the fear of death.

Keywords: Anthropopractice, Man, Soul, Schemes; Problematic Situations;

Culture; Language; Artistic Ontology; Interpretation

The

pyramids of pharaohs and tombs of the Ancient Egyptian elite contain

picturesque and sculptural images of the patrons, their relatives, servants,

houses, economic activities, as well as burial rituals; we would now

retrospectively classify them as the first realization in the history of

European culture (the culture of the “Ancient Kingdoms”) of art and practical

psychology. The questions, however, are: was this art as we understand it today

and can burial practices be likened to practical psychology? Let us postpone

these questions for now and first characterize the factual side of the matter,

namely, the representation of man by himself at that time. Specifically, this

representation was expressed by the word “soul,” which originated from the

previous, archaic culture.

The

meaning and senses of the soul were different, varying across different

countries, among different ancient peoples and in different periods, but in

theoretical cultural studies, invariant meanings of this representation can be

reconstructed1. The soul was

understood as life (whoever had a soul was alive), it did not die and lived in

a “house” (the body of a person, animal or in a natural element - sun, wind,

fire, river, etc.), from which it could fly out like a bird from a nest (in

dreams, illness), but, while the person lived, returned there. After a person's

death, the soul left its house forever and moved to another world - a burial

site, the land of ancestors, a temporary dwelling (among the Khanty and Mansi,

this is the “itterma,” a wooden idol 60-80 cm tall), the Tree of Life (depicted

precisely as a tree, on whose branches souls rested in the form of birds).

In

the culture of the Ancient Kingdoms, souls give way to gods, to whom souls are

now subordinate. Specifically, in Ancient Egypt, the main god is the sun god “Ra,”

and for the dead - Osiris (the god of the underworld, where souls went after

death). A god could also take life, but like a king by his command; however,

his main characteristics were different: governing man, maintaining order in

the world, protection in a broad sense (from bad souls and foreign gods). We

are accustomed to thinking that each person has one soul and if two or more, it

is a pathology2, but, judging by

historical data, ancient man thought differently (Figure 1). Again,

reconstruction in theoretical cultural studies allows us to assert that every

Egyptian believed he had five souls: an ordinary one during life and four after

death - “Ka,” “Ba,” “Shadow,” “Akh”.

Figure

1:

Ba and Shadow. Theban Tomb of Irynfer TT290

On the wall of this tomb, the Ba soul is drawn as a bird with a human head; it seems to be meeting the shadow of the deceased entering the burial. Often Ba is depicted in tombs with an erect phallus, strongly reminiscent of petroglyphs used by ancient man to explain how the groom transfers the soul of the future child into the mother's body (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Neolithic. Tiu, North Africa

Comparing such

petroglyphs with Egyptian images of Ba allows us to suggest that Ba is a

modification of the archaic soul in Egyptian culture. The sense of this

cultural transit is clear: in the subsequent culture (of the Ancient Kingdoms)

it was also necessary to understand where the child's soul in the mother's body

came from, how it got there. The groom, shooting his sperm at his bride,

transferred the child's soul into the mother's body; he, as a hunter, killing

an animal, transferred the animal's soul to the land of death or to a burial.

It turned out that the groom and the hunter were one and the same person;

consequently, marital relations were identified in archaic culture with

hunting, for which there is much evidence.

It is more difficult to

understand the function of the shadow. It was also escorted to the kingdom of

death and offered gifts. Since in Osiris's kingdom the shadow was pursued by

demon souls ("devourers of shadows"), one can think that the shadow-soul

was offered to the demons as a sacrifice (better let them eat the person's

shadow than his immortal Ka soul) (Figure 3).

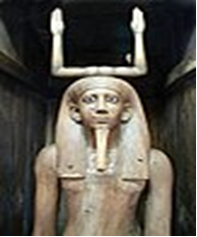

Figure 3: Statue of the Ka of Pharaoh Hor

Egyptologist Andrey

Olegovich Bolshakov in the book “Man and his Double.” Looking at the pharaoh,

his courtiers, possessing power quite comparable to the power of the Egyptian

king, although he was considered the living sun god Ra, also began to dream of

continuing life after death. In response, the priests developed a scenario to

realize this dream: for services to Egypt (which could always be found for

representatives of the elite), the priests asked the gods to create a second

soul for the patron – Ka, which was placed in the picturesque and sculptural

images of the petitioner (for this, masters and artists, often over many years

and for a lot of money, created these images beforehand). Gradually, an

esoteric practice of creating a second soul developed, the so-called ritual of “Opening

the Mouth and Eyes.” The priest touched the eyes and mouth of the patron's

images with a chisel (a burin or a rod), asked the gods to create a second

soul, uttering a text of mythological character, as, for example, is carved on

one stele: “The face of so-and-so is opened, that he may see the beauty of the

god, during his good procession, when he goes in peace to his palace of joy...

The face of so-and-so is opened, that he may see Osiris, when he becomes

justified in the presence of the two Enneads of gods, when he is at peace in

his palace, his heart is satisfied forever3”.

From that moment, the patron had a second soul, Ka, which lived on in his

images even after his death, although the first one went to Osiris's kingdom.

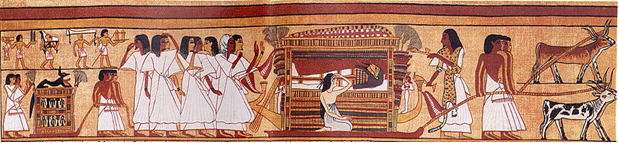

The setting of the “Opening

the Mouth and Eyes” rite can be partly understood by examining the pictorial

narrative of the scribe Ani's send-off to Osiris's kingdom (Figure 4)4.

Figure 4: …O you who admit flawless souls into the Hall of Osiris!

May you admit the flawless soul of the deceased scribe Ani,

who has triumphed [in

the Hall of Double Truth], to enter with you into the house of Osiris!

May he hear what you

hear; may he see what you see;

may he stand when you

stand; may he sit as you sit! (Concept)

Now, what is Akh? One

interpretation of this soul is as follows: Akh is immortal, born after a

person's death from the fusion of Ba and Ka, goes to the sky to join the gods.

The sky goddess instructs the deceased so-and-so: "Find your place in the

heavens, / Among the stars, / For you are the Lone Star, the companion of Hu!

You will look down upon Osiris, as he commands the spirits… / You are not among

them, you must not be among them!" (Ibid.) This text suggests that the Akh

soul belongs only to the chosen ones (“You are not among them”), perhaps the

first esotericists who identified themselves with the gods.

How can these facts be

interpreted theoretically? I propose a semiotic explanation: the souls of the

Egyptian man and what we take for works of Egyptian art are objectifications in

the culture of the Ancient Kingdoms of “semiotic schemes” that allow

understanding certain “anthropopractices.” The general functions of a scheme

are as follows. A scheme allows resolving “problematic situations,” ensures

understanding of what is happening, sets a new vision and reality, as well as

the possibility of new action5. A

simple example is the scheme of the Moscow Metro.

As a concept, the “scheme”

known to everyone as a graphic image with explanatory text is a scheme only in

the case of a special reconstruction. Namely, it is necessary to restore the “problematic

situation” whose resolution forced the invention of this scheme, the “reality”

set by this scheme, the “new actions” that this scheme allows to construct. In

this case, the problematic situation for the designers was the need to organize

passenger flows in the metro and help an individual visitor navigate it (enter

and exit at the right stations, make transfers, build routes, etc.). The

reality of the metro, set by this scheme, is not a construction and complex

technical device, but a spatial structure of station entrances and exits,

routes, transfers. The metro scheme allows the visitor to navigate and use the

metro. In other words, the “scheme of Moscow metro lines” by itself is a scheme

in the ordinary sense, i.e., a conventional simplified image of a complex

phenomenon, while the graphic image with explanatory text, included in the

reconstruction where the problematic situation, reality and new actions are

restored, is a scheme as a semiotic concept that allows understanding the

essence of the phenomenon that interested the researcher.

Accordingly, for Ka,

the problematic situation was the desire of representatives of the ancient

Egyptian elite to live forever and in the same status. The concept of Ka,

developed by the priests, plus the images of the patron created by Egyptian

masters and artists - these are schemes (narratives) setting a new

understanding and vision (a new reality) - the Ka soul. The rituals of giving

birth to Ka, feeding it, communicating with it - are new actions.

Bolshakov shows that

light, as well as food, were the two main conditions for the afterlife of Ka.

That is why sacrifices (mainly food) had to be brought to Ka and lighting of

burial chambers ensured. Thus, the life and well-being of Ka depended entirely

on the living. The representation of Ka, Bolshakov asserts, is closely

connected not only with images (statues and wall reliefs and drawings) but also

with a person's name. “The image of a person is almost always accompanied by

his name and titles, clarifying the identity of the depicted, as if being a

component part of the name <…> the image is clarified by the name, the

name is supplemented by the image.” Semantically, Ka is a root word with a wide

variety of words - name, light, illumination, reproduction, pregnancy, work,

food, gardener, sorcery, thought, god.

For Ba, problematic

situations can be considered the desire to understand what death, illness,

dreams, rock images of people and animals and later souls of natural and social

phenomena represent (Rozin, 2019). For example, Australian aborigines drew the

soul of the wind as a spiral (obviously, similar to how a whirlwind twists dust

into a spiral) and many primitive peoples invented a narrative to explain an

eclipse, in which the eclipse was explained by an attack on the luminary by a

giant predator. “In the Tupi language,” writes E. Tylor, “a solar eclipse is

expressed by the words: ‘the jaguar has eaten the sun.' The full meaning of

this phrase is still shown by some tribes by shooting flaming arrows to drive

away the fierce beast from its prey6”.

Here the spiral and the narrative of the jaguar attack are schemes. Above we

gave a graphic scheme explaining where the mother gets the child's soul from.

The problematic

situation for the shadow was probably the desire to protect Ka in Osiris's

kingdom from demons and for Akh - to assert oneself as chosen (an esotericist).

It is worth noting that

the schemes do not depend on each other; accordingly, the souls were also

understood as independent. It is difficult to say what relations the Egyptians

established between them; in any case, not holistic and not systemic (holistic

discourse was invented by Plato in antiquity and systemic - only in modern

times). At best, relations of management and power were established between the

souls, which was characteristic of the social life of the ancient world. But I

think it was often more convenient to consider a person's souls as independent,

which opened up greater possibilities. By the way, by introducing the

unconscious and asserting that it is independent of consciousness, Z. Freud

rediscovered the same strategy.

What was characteristic

of the problematic situations and schemes of ancient art? First, an example -

the depiction of a pharaoh as a lion; on its chest we see the pharaoh's name,

indicated by a cartouche (an oval in which the king's name was inscribed)7 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Pharaoh's Might

Sculpture

A modern viewer would

decide that the Egyptian artist worked in the genre of symbolic art, so the

sculpture is a symbol of the pharaoh's might (strong as a lion, king of beasts,

essentially, of course, of people). But a man of Ancient Egypt saw something

else - before him was the soul of the pharaoh in the form of a lion. Let me

explain. The point is that man of the culture of the Ancient Kingdoms in the

field of art inherits the vision of the previous, archaic culture. In the

latter, as I show, works were understood very peculiarly - images of people and

animals were understood as evoking the corresponding souls, which can be

understood by recalling the soul scheme. Indeed, people and animals are

visible, but they are not physically present, obviously these are souls. In

this case, it is clear that to evoke a soul, for example, of a person, one

needs to draw him or make his sculpture. And to send the soul back, the created

image needs to be damaged, destroyed, which was practiced for many thousands of

years. For example, if the transgressions of a deceased official were revealed,

the pharaoh ordered the destruction of his Ka images in the tomb. So, within

this conceptualization, what did the Egyptian see in the lion-pharaoh? Before

him appeared simultaneously the lion and the king's soul as a single living

being. Not a symbol, not an image, but a lion-pharaoh; this is difficult for us

to understand, but I think for ancient man it was a relatively ordinary matter

(it is no accident that people in trouble hugged sculptures of gods and called

upon them for help).

Conclusion

Now

we can return to the questions posed above: can we speak of art in Ancient

Egypt and also liken the considered practices to practical psychology?

Naturally, no. Art in our understanding had not yet taken shape and its content

was different. Yes, the Egyptian artist used painting, sculpture, architecture

and music when creating his works, believing that souls should not lose

anything of what they have. He created some schemes so that the soul had the

correct form, colour and appearance, others - matter and corporeality, third -

a proper house, fourth - the correct sound. To omit something meant to harm the

soul and anger the gods. In this respect, the ancient artist was, of course,

more responsible and fearful than the modern one.

Of

course, it is also difficult to speak of psychological practice, since the

concept of psychology would take shape almost three millennia later. However,

in function – helping to overcome various phobias – ancient burial practices

and art resembled psychological assistance and therapy.

References

1.

Rozin VM. Theoretical

and Applied Culturology. 2nd ed. Moscow: LENAND

2019:400.

2.

Rozin VM. The

Phenomenon of Multiple Personality. Based on Daniel Keyes' the Minds of Billy

Milligan. 2nd ed. Moscow: URSS 2013:200.

3.

Bolshakov AO. Man

and his Double. St. Petersburg: Aletheia 2001:288.

4. Concept

of the Soul. Ancient Egypt 2021.

5.

Rozin VM. Introduction

to Schemology: Schemes in Philosophy, Culture, Science, Design.

Moscow:

URSS 2011:256.

6. Tylor

EB. Primitive Culture. Moscow:

Sotsek giz 1939:602.

7.

Pharaoh's Lion 2024.