Unmasking Vulnerabilities in the Age of COVID-19: A Comprehensive Review

Graphical Abstract

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, driven by the novel

coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has evolved into an unprecedented global health crisis,

encompassing zoonotic origins, a shift in human-to-human transmission dynamics

and global dissemination, The review navigates through the complexities of

COVID-19. Beyond mild respiratory symptoms, the clinical spectrum includes

severe conditions like multi-organ failure, pneumonia and acute respiratory

distress syndrome (ARDS). Critical evaluation of COVID-19 diagnostic

techniques, including PCR, antigen tests and serological assays, emphasizes

their pivotal role in disease detection, management, contact tracing and

containment. In the therapeutic domain, the review explores treatments such as

antivirals, immunomodulatory therapies and repurposed pharmaceuticals, with a

spotlight on vaccine development for epidemic containment and herd immunity.

Despite progress, global healthcare systems face formidable challenges,

including equitable vaccine distribution, disinformation combat, viral mutation

management and strategic planning for future outbreaks. A comparative analysis

of SARS highlights the need to distinguish between these diseases for effective

epidemic management. The study aims to provide profound insights into the

diverse nature of COVID-19, fostering a deeper understanding and guiding future

research and public health initiatives.

Keywords: COVID-19, Zoonotic spillover, Pandemic, Emerging variants, SARS-CoV-2, Vaccine,

Clinical manifestations

1. Introduction

The

SARS-CoV-2 virus, which caused the SARS epidemic in 2002–2004, is the source of

the current pandemic, which is still lurking. Real-time observation of ongoing

evolutionary processes has provided a significant understanding of SARS-CoV-2

diversification. Numerous variations have emerged as a result of this

diversification, each set apart by unique traits like immunological evasion,

severity and transmissibility. Changes in immune profiles, human migration and

infected individuals are all part of the complex evolutionary path that is

intimately connected to ecological dynamics and the events of transmission1. Among the 180 identified species of RNA viruses capable

of infecting humans, an average of two new species emerge each year. RNA

viruses have extensively spread among humans, other mammals and occasionally

birds, across both epidemiological and evolutionary timelines. Notably, 89% of

human-infective species are zoonotic and a considerable proportion of the

remaining species trace their origins back to zoonotic sources. The pace at

which mutations are created and propagated across populations is the most

important factor in viral evolution2. Natural selection also helps to fix favourable

mutations and improve transmissibility3. However, viral evolution becomes complicated when

viruses reproduce and develop inside humans while adapting to effective human-to-human

transmission. As viral lineages evolve, antigenically distinct strains may

emerge at higher organizational levels4. This article aims to explore the evolutionary dynamics

of SARS-CoV-2 across various scales. This encompasses examining the stages of

the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) pandemic, identifying crucial factors

influencing the virus's evolution, exploring hypotheses surrounding the

emergence of statistically significant variants and contemplating potential

evolutionary pathways that could impact public health in the future.

Considering the substantial role of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in triggering the

COVID-19 pandemic, a comprehensive investigation into the infection and its

repercussions for public health is essential. The review also delves into the

transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from patient to host, the utilization of

mathematical models for predicting the risk of viral aerosol/droplet

transmission, potential pathways for viral entry into the human host and the

cellular mechanisms underlying these processes.

Also,

highlights COVID-19 clinical symptoms and available diagnostic approaches for

detecting the virus. The requirement for effective treatment techniques, such

as vaccine development and medication repurposing, is emphasized here. Given

the considerable study on COVID-19 and the available literature, it appears difficult

to address every element. The article offers a comprehensive examination of

diverse facets concerning the COVID-19 outbreak. It covers a wide range of

topics, such as preventative measures against the virus, clinical

characteristics of symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, estimations of the

infection and incubation periods, the immune responses that the virus elicits

in humans and the relationship between pre-existing comorbidities and COVID-19

mortality. Furthermore, the article provides a historical framework for understanding

pandemics, tracing their evolution from confined outbreaks to global epidemics,

starting in the 16th and 19th centuries. It delves into zoonotic origins,

elucidating the transmission of zoonoses from animals to humans, with

illustrative examples like HIV/AIDS, Ebola and historical influenza strains. The

SARS-CoV-2 virus exhibits significant genetic similarities to pangolin

coronaviruses and bat betacoronaviruses, indicating that the ongoing COVID-19

pandemic has its origins in an animal reservoir5. As the battle against COVID-19 continues, the

acquisition of knowledge and understanding remains indispensable in formulating

efficacious strategies to safeguard global public health.

2. Emergence and spread of COVID-19 (coronavirus

disease 2019)

Several

pneumonia cases with an unclear cause emerged in late December 2019, in Wuhan,

Hubei Province, China6. The afflicted individuals exhibited

clinical signs of fever, cough, dyspnea, chest pain and bilateral lung

infiltration, symptoms of viral pneumonia, which were comparable to those in

SARS and MERS7. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, a wet

market in Wuhan's downtown known for selling seafood and live animals,

including poultry and wildlife (Figure 1), was linked to the majority of

the initial cases8. On December 8, 2019, the earliest case was recorded9.

Figure 1: The

figure represents the sequence of COVID-19 events recorded. The severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2, has been identified as the

causative agent of COVID-19 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of

Viruses (ICTV). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a public health

emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

World

Health Organization (WHO) was formally notified that the Wuhan Municipal Health

Commission reported an unknown pneumonia outbreak on December 31. Independent

Chinese scientific teams revealed a novel beta coronavirus as the cause of this

newly discovered disease10. The first genome sequence of the novel

coronavirus was made available on January 10. The outbreak coincided with the

Lunar New Year celebrations, which led to more people traveling and spreading

the virus to additional Hubei province cities and ultimately to other regions

of China11. The escalation in severity led the World

Health Organization (WHO) to declare the COVID-19 outbreak as a public health

emergency of international concern on January 3012. WHO officially designated the illness as COVID-19 on

February 1113. (Figure 1) shows the timelines of these

events. China imposed strict public health measures, such as a city-wide

lockdown of Wuhan on January 23 with travel and transportation restrictions, to

contain the outbreak14. The virus's high transmissibility and

global travel contributed to large clusters of infections being reported in

numerous countries. Consequently, on March 11, 2020, the World Health

Organization (WHO) formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic15,16. China was able to contain the virus quite well, but

cases in the USA and Europe increased drastically17.

3. SARS and COVID-19: Similarities and differences

There are

notable similarities between the clinical manifestations and modes of

transmission of the 2019 COVID-19 and the SARS (severe acute respiratory

syndrome) virus. Both infections have the potential to manifest as rapidly

progressing pneumonia. It seems that the primary mode of transmission for both

is infectious respiratory droplets that are released from mucosal membranes (Table

1). The viruses show comparable stability and degradation in aerosols and

on various surfaces18. According to researchers, both viruses can

live for up to two days on stainless steel and three days on plastic and their

viral titers on both surfaces show comparable decay patterns19-21. Both SARS and COVID-19 seem to have a median incubation

period of 4 to 7 days from first exposure to the start of symptoms.

Furthermore, according to research, the maximum incubation time for both might

be up to 14 days22-24. This longer incubation time adds to the

difficulty of preventing the spread of these illnesses. Despite these

similarities, it is important to emphasize that SARS and COVID-19 are caused by

different viruses and are members of separate coronavirus subfamilies. In

summary, whereas SARS and COVID-19 share clinical signs and transmission

characteristics, they are caused by separate viruses and have distinct

characteristics that distinguish them as distinct causative agents.

Understanding these similarities and differences appears critical for

successful epidemic management and prevention measures. The incubation time and

length of viral shedding are critical for determining the risk of transmission,

adopting isolation and quarantine measures and developing effective antiviral

therapies for patients. According to recent epidemiological studies, the

typical period of COVID-19 virus shedding is around 20 days, with some

survivors shedding for as long as 37 days25. In contrast, viral RNA remained detectable in non-survivors

until death. Severe COVID-19 patients may suffer viral shedding for a median of

31 days after the disease starts26.

Table 1: SARS and COVID-19 comparisons: green highlights

similarities, yellow highlights differences from COVID-19 and orange highlights

feature specific to COVID-19.

|

SARS

COVID-19 | ||

|

Pre-transmissibility |

NO |

YES |

|

Mild

case transmissibility |

NO |

YES |

|

Reproduction

Number |

1.7-1.9

(WHO) |

2.0-2.5

(WHO) |

|

Number

of reported cases |

More

than 8000 |

692.52

million (July 31, 2023) |

|

Number

of reported deaths |

774 |

6,903,467

(July 31, 2023) |

|

Mortality

rate |

9% |

3.1% |

|

The

primary mode of transmission |

Infectious

respiratory droplets dispersed from mucous | |

|

Ability

to survive on surfaces |

YES | |

|

Median

incubation period |

4-7

days | |

|

Maximum

incubation period |

14 days | |

|

Potential

to cause severe respiratory infection |

YES | |

|

Potential

to infect CNS and brain |

YES | |

Betacoronaviruses and alphacoronaviruses have

important natural hosts in bats. RaTG13, a bat coronavirus isolated from Rhinolophus affinis in Yunnan

province, China, is the closest known match to SARS-CoV-2 to date27. RaTG13

and SARS-CoV-2 share 96.2% of the full-length genome sequence, demonstrating a

strong genetic similarity28,29. The fact

that SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 share over 90% of their genome's sequence, including

the variable S and ORF8 regions, is especially remarkable28. Their

close relationship is highlighted by phylogenetic analysis, which lends

credence to the theory that bats are the original host of SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2

and “RmYN02,” a recently discovered coronavirus found in a Yunnan Rhinolophus malayanus bat, share

93.3% of their genome29.

Interestingly, it shares a longer 1ab gene with SARS-CoV-2 with 97.2% identity,

higher than RaTG1330. Furthermore,

ZC45 and ZXC21, two additional bat coronaviruses that were previously

discovered in eastern Chinese Rhinolophus

pusillus bats, are members of the SARS-CoV-2 lineage within the

Sarbecovirus subgenus31. These

findings highlight the wide range of bat coronaviruses that are strongly

associated with SARS-CoV-2, indicating that bats may be the virus's possible

hosts. Recent investigations reveal that the genetic diversity observed in

SARS-CoV-2 and its related bat coronaviruses stems from over 20 years of

sequence evolution. Consequently, it is incorrect to categorize these bat

coronaviruses as the immediate progenitors of SARS-CoV-2, despite being likely

evolutionary ancestors.

Pangolins are another possible animal host

connected to SARS-CoV-2. Between 2017 and 2019, several viruses related to

SARS-CoV-2 were discovered in the tissues of pangolins32. These

pangolin viruses are from two distinct sub-lineages and were independently traced

in the provinces, of Guangxi and Guangdong33-37. Pangolins

linked to various smuggling incidents have been found to have

SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus infections, suggesting that these animals may

serve as hosts for the viruses38. Pangolins

infected with coronaviruses displayed clinical symptoms and histological

changes such as multiple organ infiltration of inflammatory cells and

interstitial pneumonia, in contrast to bats, which typically carry the virus

without obvious damage39.

Emerging coronaviruses that are derived from bats

require an intermediate host to proliferate. For example, dromedary camels and

palm civets served as intermediary hosts for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively40. The

viruses harboured by these hosts share a genome sequence identity of over 99%

with the corresponding viruses in humans41. The role

of an intermediary host in the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is

accountable for the COVID-19 pandemic, is under scrutiny and remains unclear.

Pangolin coronaviruses exhibit only a 92% genomic identity with SARS-CoV-2,

despite displaying a remarkably similar receptor-binding domain (RBD)42.

Consequently, it is challenging to definitively ascertain whether pangolins

acted as the intermediate host for SARS-CoV-2 or if they were directly

implicated in the virus's emergence. The animal source of SARS-CoV-2 is

presently poorly understood, with limited knowledge available on this aspect.

The virus's reservoir hosts have not been identified, nor it has been

determined if an intermediate host was involved in the virus's transmission to

humans. Significantly, the discovery of pangolin coronaviruses, RaTG13 and

RmYN02 implies that SARS-CoV-2-like coronaviruses are prevalent in animals43-44.

In addition to wildlife, research has explored the

susceptibility of domesticated and laboratory animals to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Experimental findings have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 can effectively

replicate in cats and ferrets, particularly in the upper respiratory tract.

Conversely, dogs, pigs, chickens and ducks have exhibited immunity to the virus45. Notably,

minks have been observed to contract SARS-CoV-2, as evidenced by an outbreak on

mink farms in the Netherlands, leading to severe cases of respiratory distress

and interstitial pneumonia46. Although

devoid of symptoms, two dogs in Hong Kong tested positive for spontaneous

SARS-CoV-2 infection through serological and virological tests47. Similarly,

blood samples from cats in Wuhan showed the presence of neutralizing antibodies

against SARS-CoV-2, confirming the infection in cat populations. However, the

possibility of transmission from cats to humans is still uncertain48. Ongoing

comprehensive research and surveillance on animal susceptibility aim to provide

a deeper understanding of potential hosts and transmission dynamics of the

virus.

4. Comparative insights into SARS-CoV-2:

Infectiousness, transmission and evolution

The virus

accountable for acute respiratory illness, SARS-CoV-2, belongs to the

coronavirus family and carries a non-segmented genome composed of

positive-sense, single-stranded RNA enveloped by the viral capsid49. Coronaviruses (CoVs) are categorized into four genera:

α, β, γ and δ-CoV50. While α- and β-CoV predominantly infect

mammals, they can also affect birds. Human-infecting coronaviruses include

HCoV-229E, SARS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, MERS-CoV and HCoV-HKU151. Infections caused by HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1

and HCoV-OC43 typically result in mild respiratory symptoms, whereas SARS-CoV

and MERS-CoV can lead to severe respiratory disease, occasionally resulting in

death due to multiple organ failure52. SARS-CoV-2 shares notable similarities (over 85%) with

bat-derived SARS-like coronaviruses identified as bat-SL-CoVZC45 and

bat-SL-CoVZXC2153. In comparison to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, it demonstrates

approximately 79% and 50% homology, respectively54. This evidence, combined with phylogenetic research,

strongly indicates that SARS-CoV-2 originated in bats and potentially

transmitted to humans through an unidentified intermediate host species. (Figure

2) illustrates the genomic structure, encoded structural and non-structural

proteins and the primary host of SARS-CoV-2.

The

pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 involves a complex interplay of viral and host

factors. As an enveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, the genomic

structure of SARS-CoV-2 comprises a significant portion (two-thirds) dedicated

to an open reading frame (ORF 1a/b), encoding 16 non-structural proteins (NSPs)

crucial for replication. The remaining section of the genome encodes essential

structural proteins (Spike glycoprotein, Small Envelope protein, Matrix protein

and Nucleocapsid protein) and accessory proteins with functions still under

investigation. The S glycoprotein, essential for host cell entry, binds to the

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. However, the precise mechanism

of membrane invagination for SARS-CoV-2 endocytosis remains unclear. Host

factors, particularly ACE2 expression, influence viral tropism. The elderly and

individuals with underlying health conditions are more susceptible to severe

infections, partly due to age-related immune system changes and comorbidities.

Host immune responses, both innate and adaptive, play a crucial role and

dysregulated responses can contribute to disease severity. Additionally,

genetic factors contribute to interindividual variability in susceptibility and

disease outcomes. A comprehensive understanding of these viral and host

elements is crucial for developing effective therapeutic interventions and

vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Ongoing research continues to unveil additional

details about the intricate virus-host interactions shaping the pathogenesis of

COVID-19. Without a doubt, expressive experimentation has shown that the virus

infects people by attaching itself to respiratory system-expressed ACE2

receptors55,56. Overall, findings from several

investigations show that SARS-CoV-2 is extremely infectious, with viral

shedding commencing before symptoms develop and the virus spreading through

many channels. Controlling the disease's spread is a key problem for public

health initiatives.

SARS-CoV-2

is less severe in terms of morbidity and mortality than MERS and SARS, but it

is more contagious. COVID-19 has a much lower mortality rate of 3.4% compared

to 9.6% and 35% for SARS and MERS, respectively. COVID-19 primarily spreads

through person-to-person contact, particularly between close friends and family

members57. Numerous studies demonstrate the critical

role symptomatic individuals play in COVID-19, mainly through respiratory

droplet expulsion from actions like coughing or sneezing. On the other hand,

nosocomial transmission was primarily responsible for the spread of MERS-CoV

and SARS-CoV among healthcare personnel58. In MERS-CoV outbreaks, medical staff was responsible

for 62%-79% of cases, whereas in the SARS case, they accounted for 33%-42% of

cases. The most likely ways for a virus to spread are through direct contact

with the host or interactions with an unidentified intermediate carrier59.

Figure 2: The

figure represents the structural and genetic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2.

Numerous structural proteins, including the spike glycoprotein (S), envelope

(E), matrix (M) and nucleocapsid protein (N). The genetic segment ORF1ab

encodes several non-structural proteins (nsp 1–16) concurrently. The

host-related variables that can affect an individual's susceptibility to and

the severity of a SARS-CoV-2 infection are listed in the lower section.

The

SARS-CoV-2 virus changes in a variety of ways as it grows and spreads among people.

In December 2020, a noteworthy variant, VUI-202012/01, was examined due to 17

distinct alterations or mutations in its DNA. Since the discovery of the

SARS-CoV-2 virus in 2019, thousands of mutations have already manifested in its

genome60. As the pandemic continues, the continual mutation process

in the population may result in the production of immunologically relevant

mutations, thereby affecting vaccination effectiveness. These mutations are

resulting in novel viral combinations. The COVID-19

genomics UK consortium (COG-UK)

has conducted extensive epidemiological and virological investigations in

response to the significant surge in COVID-19 cases recently observed in the

United Kingdom (UK), particularly in South East England61. A novel variant was identified in viral genome sequences, forming a

distinct phylogenetic grouping. This variant is distinguished by multiple spike

protein mutations (deletion 69-70, deletion 144, N501Y, A570D, D614G, P681H,

T716I, S982A and D1118H), accompanied by alterations in other genomic regions62. Although viral mutations are normal, preliminary studies show that

this variant in the UK may be critical for increased transmissibility and is

projected to possibly raise the reproductive number by 0.4 or more63. Notably, this new variety evolved during a period of increased family

and social gatherings. However, there is no indication that it causes more

severe infections than other variations.

5. Role of ACE-2 Receptor, an Angiotensin-Converting

Enzyme

SARS-CoV-2

gains entry into the human host through receptor-mediated endocytosis, a

mechanism where viruses bind to specific receptors on the host cell's surface,

facilitating entry. The virus's receptor-binding domain establishes a

connection with the appropriate receptor on the host cell, enabling entry. Both

SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 utilize the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2)

receptor to infect cells. Earlier studies have shown that the S-protein of

SARS-CoV exhibits a strong affinity for the ACE-2 receptor, serving as the

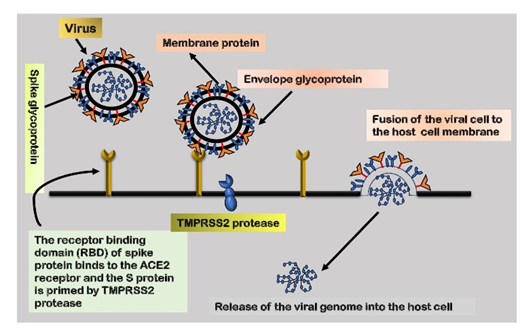

entry point for the virus into host cells64. Figure 3 depicts the fusion of the virus with the host

receptor.

The entry

of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells is also mediated by S-protein priming by transmembrane

protease serine-2 (TMPRSS2). This priming event is crucial for the fusion of

the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, enabling subsequent viral

entry. Therefore, the coordinated interplay between the ACE-2 receptor and

TMPRSS2 is essential for the efficient entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host

environment. It is noteworthy that TMPRSS2 exhibits higher expression and

broader distribution compared to ACE-2 receptors, suggesting that ACE-2 may act

as a limiting factor during the initial infection phase. While TMPRSS2 is a key

component for viral entry, alternate proteases, such as cathepsin B/L, may act

as substitutes for TMPRSS2. Hence, the simultaneous inhibition of these

proteases becomes crucial in preventing cellular entry.

The

structural characteristics of the S-proteins of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2

facilitate the entry of the latter into cells65. Studies involving human HeLa cells and animals with and

without ACE-2 expression support the involvement of ACE-2 receptors in the

cellular entry of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, particularly the Wuhan strain66. Research on SARS-CoV-2 infection of BHK21 cells

indicated higher infection rates when transfected with human and bat ACE-2

receptors compared to BHK21 cells lacking ACE-2 expression67-69. Biophysical and structural data suggest that the ACE-2

binding affinity of the SARS-CoV-2 S-protein ectodomain is significantly

greater than that of the SARS-CoV S-protein by a ratio of 10:2070. This difference is believed to contribute to the

variance in contagiousness between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Although the ACE-2

and ACE-1 receptors share similarities, the ACE-2 receptor has a smaller active

site and a smaller binding pocket with different amino acids, making it

resistant to typical ACE inhibitors such as lisinopril, enalapril and ramipril71.

Furthermore,

there is no evidence suggesting that angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), like

losartan, disrupt the activity of ACE-2. TMPRSS2, identified as a type II

transmembrane protease, consists of distinct domains, including an

intracellular N-terminal domain, a transmembrane domain, an extracellularly

extending stem region and a C-terminal domain facilitating its serine protease

(SP) function72. The serine protease activity relies on a

catalytic triad, comprised of His296, Asp345 and Ser441, responsible for

cleaving basic amino acid residues, particularly lysine or arginine residues,

aligning with its role in cleaving the S1/S2 site in SARS-CoV-273.

While

TMPRSS2 has been recognized for its involvement in prostate cancer and viral

infections such as influenza, SARS and MERS, it has recently gained attention

from drug developers. Multiple studies are underway to uncover strategies aimed

at reducing TMPRSS2 expression or blocking its activity in host cell membranes,

with the ultimate goal of inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 entry into host cells74,75.

Figure 3: A

representation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with the host receptor and the

subsequent fusion of the viral cell with the host cell membrane.

6. Diagnostic, Therapeutic Approaches and

Strategies to Inhibit Viral Entry

Molecular

detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid is the most accurate diagnostic approach72. Various commercially available kits for viral nucleic

acid detection target different genes, including ORF1ab (containing RdRp), N, E

or S73. The detection time may vary from a few

minutes to several hours depending on the technology utilized. Although

SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in throat swabs, posterior oropharyngeal saliva,

nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum and bronchial fluid, the virus load is notably

higher in samples from the lower respiratory tract74. Viral nucleic acid has also been detected in intestine and

blood samples, even in cases where respiratory tests yielded negative results.

The viral load may decrease from its peak at the onset of the illness,

potentially leading to false negatives when using oral swabs75. It is advisable to employ multiple detection techniques

to confirm a COVID-19 diagnosis.

To

address the issue of false negatives, alternative detection approaches have

been utilized. Therefore, for individuals with a robust clinical suspicion of

COVID-19 despite an initial negative nucleic acid screening, a combination of

CT scans and repeated swab testing has been recommended. Serological assays

that identify antibodies to the N or S protein of SARS-CoV-2 could complement

molecular diagnosis, particularly in the latter stages of the illness or for

retrospective research76,77. The magnitude and duration of immunological

responses are still unknown and the sensitivity and specificity of existing

serological assays vary. When choosing and interpreting serological testing,

all of these factors should be taken into consideration, possibly even

extending to future assays for T-cell responses.

As of

right now, neither COVID-19 nor specific antivirals that target SARS-CoV-2 have

the potential to combat the disease. However, several treatments have shown

some promise. Manufacturers and researchers are undertaking large clinical

studies to examine new COVID-19 therapy options. As of October 2, 2020, over

405 therapeutic medicines were being developed for COVID-19, with almost 318 of

them undergoing human clinical trials78. Potential antiviral target for the treatment of

COVID-19 is depicted in (Figure 3).

A crucial

strategy in combatting SARS-CoV-2 infection is to hinder viral entry.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) exists in membrane-bound ACE2 (mACE2),

located in the gallbladder, heart, intestines, kidneys and testes79. The virus uses human proteases as entry activators to

break through host cells through membrane fusion and it uses ACE2 as a

receptor. Treatments aimed at this entry mechanism have the potential for

treating COVID-19. Umifenovir, also known as arbidol, is a drug approved for treating

respiratory viral infections and influenza in China and Russia. Its mechanism

of action involves preventing membrane fusion by interfering with the

interaction between the S protein and ACE279. In vitro studies have demonstrated its efficacy against

SARS-CoV-2, Clinical data suggests that it may present a more effective

treatment for COVID-19 when compared to lopinavir and ritonavir80-84.

One

notable drug that shows promise is camostat mesylate, which is licensed in

Japan to treat postoperative reflux esophagitis and pancreatitis85. Previous studies have demonstrated the ability of

camostat mesylate to inhibit TMPRSS2 activity and protect mice from fatal

SARS-CoV infection86,87. Recent studies have further indicated that

camostat mesylate can inhibit the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into human lung cells88. This suggests potential utility as an antiviral drug

against SARS-CoV-2 in the future, although further clinical data is required to

confirm its effectiveness.

Other

drugs used to treat autoimmune diseases and prevent malaria, such as

chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, may also influence SARS-CoV-2 entry. They

work by preventing membrane fusion by raising endosomal pH, interfering with

the interaction between virus and host receptor and inhibiting the

glycosylation of cellular receptors89-91. Regarding their effectiveness in treating COVID-19, there

remains a lack of scientific consensus. Despite concerns about an increased

risk of cardiac arrest in treated patients, two clinical investigations found

no correlation between these medications and patient mortality rates92,93. On June 15, 2020, due to documented adverse events, the

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revoked the emergency use authorization

for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 therapy94.

Another

therapeutic approach involves the use of soluble recombinant hACE2, specific

monoclonal antibodies or fusion inhibitors targeting the SARS-CoV-2 S protein

to prevent its binding to the ACE-2 receptor95. Examples of replication inhibitors include remdesivir

(GS-5734), favilavir (T-705), ribavirin, lopinavir and ritonavir. The remaining

three agents act on RdRp, except for lopinavir and ritonavir, which inhibit

3CLpro. (Figure 4) illustrates potential antiviral targets for COVID-19

treatment. However, further clinical research is necessary to evaluate the

effectiveness and safety of these approaches.

Figure 4: Potential

antiviral interventions against the SARS-CoV-2. In addition to antiviral agents

immunomodulatory and immunoglobulin-based medications are potential treatments.

Key molecular targets implicated in the viral replication cycle and potential

treatments include ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2), crucial for the

virus's initial interaction during receptor binding; 3CLpro (3C-Like Protease),

a protease inhibited by lopinavir and ritonavir; CR3022, a human monoclonal

antibody targeting the SARS-CoV virus; Envelope Protein (E), a potential target

for disrupting viral replication; Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), involved in

various stages of viral replication and a potential therapeutic target; gRNA

(Genomic RNA), a critical component of the viral replication process; HR2P

(SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Derived Peptides, Hepatod Repeat 2), peptides

considered for their potential in inhibiting viral fusion; ISG

(Interferon-Stimulated Gene), targeted by immunomodulatory agents to modulate

the host immune response; M (Membrane Protein), a potential target for

disrupting viral replication; RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase or RdRp, the key

enzyme in the viral replication process targeted by antiviral agents such as

remdesivir, favilavir and ribavirin; sgRNA (subgenomic RNA), involved in

various stages of the replication cycle; S (Spike Protein), a major target for

therapeutic intervention considering its role in receptor binding and viral

entry; and TMPRSS2 (Transmembrane Protease Serine Protease 2), facilitating

viral entry into host cells and a potential target for antiviral strategies.

7. Current Management approaches for COVID-19

Avoiding

transmission should be the primary objective of COVID-19 treatment, especially

in those with moderate symptoms, given the uncertainty surrounding the

effectiveness of currently available antiviral medications. Individuals

receiving at-home care must be closely monitored and if their health worsens,

therapy must be escalated right away. Studies on the advantages of

corticosteroids, weighing anti-inflammatory effects with possible hazards of

viral replication, have shown conflicting findings96. Corticosteroids may, however, be taken into

consideration in situations when there are other signs, such as severe COPD.

Inhalers are used over nebulized medicines, which produce aerosols, to reduce

the danger of airborne viral dissemination97. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have

generated controversy because of their ability to affect epithelial cell ACE2

receptor levels and perhaps worsen viral infection98. The specific effects of NSAID usage in COVID-19 remain

uncertain. Some suggest that NSAIDs might elevate the risk of acute respiratory

distress syndrome (ARDS) by triggering leukotriene release and

bronchoconstriction99. However, the application of NSAIDs for

symptom management should be tailored to each individual. Presently, the European

Medicines Agency (EMA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) do not advise

against the use of NSAIDs100. In hospital settings, acetaminophen is

often preferred over NSAIDs to minimize the risk of bleeding and kidney damage101.

Controversy

has arisen regarding the use of angiotensin receptor blockers and ACE

inhibitors in COVID-19. Nonetheless, the American Society of Cardiology and the

European Society of Cardiology presently do not recommend initiating or

discontinuing these drugs102. The choice of antiviral and

anti-inflammatory therapies should be personalized according to each patient's

situation, guided by infectious disease experts and conducted within the

context of a clinical trial or registry. Oxygen therapy, encompassing methods

such as nasal cannula and high-flow oxygen, is often beneficial for individuals

with mild to severe COVID-19103. Non-invasive and invasive mechanical

ventilation are commonly needed in situations of acute respiratory failure.

Positive airway pressure (PAP) is an aerosol-generating treatment; hence

healthcare professionals had and must use a greater degree of personal

protective equipment (PPE)104. Unless there are particular

contraindications, pharmaceutical prophylaxis was used for these events and should

be made available to hospitalized COVID-19 patients due to the elevated risk of

venous thromboembolism.

8. Preventing COVID-19: Progress in vaccine advancements

Nearly

200 clinical studies were conducted to evaluate a range of innovative and

repurposed medicines in the battle against COVID-19105. Among these programs, vaccinations hold promise since they

could stop the spread of illness to a larger population. Before they may be

used widely, the safety and efficacy of these immunizations must first be

properly confirmed. It is impossible to overstate the importance of this stage

since subpar immunizations run the danger of doing more damage than good via

mechanisms including antibody-dependent augmentation. Therefore, meticulous

testing and verification are crucial before the widespread adoption of any

COVID-19 immunizations.

8.1. Technological approaches employed in the

development of COVID-19 vaccines

Numerous

technologies, were employed by scientists and researchers globally in their endeavours

to create a secure and efficient vaccine for SARS-CoV-2. Among these

technologies, gene vaccines, inactivated vaccines, viral vector vaccines and

protein subunit vaccines stand out as the most promising candidates.

8.2. Vaccines based on protein subunits

Protein

subunit vaccines, frequently administered through sophisticated systems like

liposomes, virosomes or polymeric nanoparticles, harness components of the

pathogen to stimulate the host's immune system105. Liposomes and virosomes, serve as effective adjuvants

and carriers for antigens and are commonly employed in the development of

vaccines against SARS-CoV-2106. For instance, a study reflects upon a cationic

liposome protein subunit vaccine that incorporates the S1 component of the

SARS-CoV-2 virus. This vaccine also includes two adjuvants: monophosphoryl

lipid A (MPLA), acting as a TLR4 and TLR9 agonist and CpG ODN107. The inclusion of cationic elements such as

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) enhances the interaction of

the liposome with antigen-presenting cells108. This liposome vaccine demonstrated improved T cell

immunity, activating CD4+ and CD8+ cells and promoting

IgA synthesis for potential mucosal defense109.

Virosomes,

lipid vesicles containing viral proteins, are preferred over liposomes as

adjuvants due to their ability to shield pharmaceutically active compounds from

degradation in endosomes until they reach the cytoplasm110. Virosomes have previously been utilized in the delivery

of vaccines for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. The Centre for Vaccine Development at

Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, is working on a subunit

vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. This vaccine employs a recombinant S-protein

receptor-binding domain (RBD), likely combined with alum or glucopyranosyl

lipid A (GLA), a synthetic TLR4 agonist111.

The Australia

University of Queensland and Novavax collaborated on the development of an

immunogenic virus-like nanoparticle vaccine, NVX-CoV2373, currently in phase 3

trials. This vaccine incorporates a recombinant S-protein, demonstrating

minimal reactogenicity and eliciting a T helper 1 response without significant

side effects in most individuals112. Clover Biopharmaceuticals is also working on a highly

pure S-trimer vaccine using their Trimer-Tag technology, previously employed in

subunit vaccines for HIV, RSV and Influenza. In collaboration with

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Dynavax Technologies, Clover Biopharmaceuticals has

completed enrolment in a phase 1 study, employing the CpG 1018 adjuvant, a TLR9

agonist known to activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with a

favorable safety profile113,114.

8.3. Vaccines with inactivated viruses

Weakened

bacterial or viral pathogens used in inactivated vaccinations stimulate the

immune system without actually infecting the recipient. Although these

vaccinations don't provide lifelong protection, booster injections are often

required to provide a long-term shielding effect. Large numbers of viral

particles are propagated, condensed and then made inactive using chemical

and/or physical techniques to make inactivated viral vaccines. Various

techniques, such as the application of ascorbic acid, binary ethylenimine,

gamma irradiation and high-temperature treatment, are commonly employed to

render viral particles inactive115. The efficacy of these approaches relies on ensuring

complete deactivation of the specific virus. The Wuhan Institute of Biological

Products, affiliated with the China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm),

actively worked on one of the initial inactivated COVID-19 vaccines116,117. In the development of this vaccine, the virus undergoes

growth in the Vero cell line, followed by inactivation using formalin or

β-propiolactone, with alum incorporated as an adjuvant118. All participants in the phase 1/2 clinical trials

developed antibodies in response to the vaccination, with few negative side

effects119.

The most

typical adverse effects, such as discomfort at the injection site and fever,

were modest and self-limiting. Phase 3 studies are now being conducted to

assess the vaccine's effectiveness and long-term safety. Sinovac Biotech Ltd.

in China is involved in developing CoronaVac (formerly PiCoVacc), another

inactivated vaccine. This vaccination puts genetic stability first, using the

SARS-CoV-2 CN2 strain that was isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples

of hospitalized patients. The vaccine is presently in the midst of phase 3

clinical trials, involving a participant pool of 8,870 individuals120,121. In a distinct development, the University of Wisconsin,

Madison, has collaborated with vaccine companies FluGen and Bharat Biotech to

create an inactivated vaccine named CoroFlu, designed for intranasal delivery.

Derived from FluGen's M2SR influenza vaccine, CoroFlu leverages the immune

response targeting influenza. The M2SR vaccine has been adapted to incorporate

the S-protein gene sequences of SARS-CoV-2, to elicit an immune response

against the virus122. This non-invasive nasal immunization

approach shows potential in eliciting robust mucosal and systemic immune

responses to combat respiratory virus infections, providing an alternative to

traditional invasive parenteral vaccination methods.

8.4. Adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccines

Adenoviruses,

with their icosahedral capsid and double-stranded linear DNA, are essential for

initiating both innate and adaptive immunity in mammals. By increasing

cytotoxic T lymphocytes and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, they aid in

the immune response. These lymphocytes are in charge of identifying and getting

rid of virus-infected cells123. Building on this method, adenoviral vectors

have been extensively employed to combat a variety of illnesses, including

influenza, Ebola, SARS, HIV and recently COVID-19124. Renowned academic institutions and pharmaceutical

companies including the Jenner Institute at Oxford University, CanSino

Biologics and Johnson & Johnson have led the development of COVID-19

vaccines utilizing adenoviral vectors125. Phase 2 clinical trials for CanSino Biologics' Ad5-nCoV

vaccine are presently underway and the results are promising126. This vaccine carries the genetic code for the S-protein

of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and employs the non-replicating chimpanzee adenoviral

vaccine vector, AZD1222. Noteworthy is its suitability for vulnerable

populations such as children, the elderly and individuals with pre-existing

medical conditions, as it necessitates only a single dose and triggers a

substantial immune response without causing illness127. AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford have conducted

phase 1 and phase 2 studies on AZD1222, demonstrating a promising safety

profile and the successful generation of neutralizing antibodies against

SARS-CoV-2128,129.

Adenoviral

vectors are still in the early stages of development and have not yet been

approved for use in the treatment of infectious diseases in humans, even though

they exhibit great promise for COVID-19 vaccines. Concerns have been raised

about possible inflammatory responses as reported in AstraZeneca studies. Additionally,

it's probable that people already have some amount of resistance to adenoviral

vectors owing to their frequent exposure to them. While research and clinical

trials continue, the scientific community is dedicated to developing safe and

effective medicines to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and the long COVID.

8.5. Nucleic acid-based vaccines

DNA

vaccines or mRNA vaccines, promise to be more effective than conventional immunizations.

Direct administration of DNA plasmids that encode particular target antigens

results in potent B and T cell responses with increased safety130. These vaccinations are safe for those with impaired

immune systems since they don't include any infectious organisms. Synthetic DNA

vaccines quicken the development process by enabling scalable manufacture, fast

design and preclinical testing of several candidates and simpler regulatory

approval for clinical use. Their stability at different temperatures also

guarantees a longer shelf life. Currently being developed is a gene-based

vaccine that specifically targets the S-protein of SARS-CoV-2. The vaccine

candidate from Inovio Pharmaceuticals uses DNA-plasmid pGX9501, which was

developed using MERS-CoV vaccine constructions from the past. The vaccine is

now in phase 2 clinical trials. It is given intradermally and then

electroporated131. Gene vaccines also use mRNA, which operates

in the cytoplasm without having to cross the nuclear membrane, in addition to

DNA. mRNA vaccines are less dose-intensive than DNA vaccinations and produce

strong immune system memory. However, because of their heat lability and

susceptibility to hydrolysis by circulating ribonucleases, they are less stable132. This is addressed by the formulation of mRNA vaccines

as lipid nanoparticles, which improve stability and host distribution. Examples

include the SARS-CoV-2-targeting drugs mRNA-1273 from Moderna and BNT162b1 from

Pfizer, both of which are in advanced clinical moderation133. Despite the advancements, there are still difficulties

in the global production, distribution and administration of COVID-19 vaccines.

8.6. Drugs approved for the COVID-19 treatment

Ongoing

extensive clinical trials are underway to evaluate the potential effectiveness

of several medications in treating COVID-19 patients. The selection of these

medications is based on the hypothesis that they may hinder the virus from

entering the host and replicating. Various compounds, including some that have

undergone human clinical trials, are currently under assessment in clinical

trials as potential COVID-19 treatments. Researchers are investigating the

ability of experimental drugs to impede the virus's entry into the host and

subsequent replication. While certain medications have been previously employed

in treating SAR-CoV infections, others are being utilized for the first time in

the context of SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Remdesivir,

developed by Gilead Sciences, has received FDA approval for treating COVID-19

in patients aged 12 and above requiring hospitalization. Remdesivir works by

inhibiting the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, disrupting its interaction with

the RNA of SARS-CoV-2 and thereby halting further replication134. After receiving remdesivir intravenously, 36 out of 53

COVID-19 patients showed improvement, indicating positive clinical outcomes135. Although lopinavir and ritonavir-based antiretroviral

therapy have been investigated, it has not proven to be any more effective than

standard care. Umifenovir, which has been licensed for influenza prevention in

China and Russia, is used for the treatment of COVID-19 because of its

potential to inhibit the S-protein/ACE2 interaction136.

Research

indicates that favipiravir, which inhibits RNA polymerase and is approved for

use against influenza in Japan, has a better clinical outcome in mild cases of

COVID-19 than umifenovir137. In small-scale clinical trials conducted in

China, chloroquine has demonstrated potential in slowing pneumonia progression

and viral replication in COVID-19 patients138-139. For COVID-19 patients, there is promise in the combination

of statins and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) to prevent acute

respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)140. Ongoing studies are exploring the potential benefits of

these combined treatments in managing the severe consequences of the illness (Figure

5). The strategy of employing existing, approved drugs for COVID-19

treatment capitalizes on the current pharmacopeia to swiftly address the urgent

global health crisis. This tactic comprises repurposing well-known

pharmaceuticals that were first authorized for a range of medical conditions to

target particular aspects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus or the host immune system.

Making the most of these medications' well-established pharmacokinetics,

mechanisms of action and safety profiles is the main goal.

Remdesivir,

initially developed for Ebola, is repurposed as an antiviral for COVID-19. Its

mechanism of action involves inhibiting the viral RNA polymerase, thereby

disrupting viral replication141. Lopinavir/Ritonavir, FDA-approved for

treating HIV, is being explored for its ability to inhibit the 3CLpro enzyme in

SARS-CoV-2, disrupting viral replication142. Agents with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory

properties, such as dexamethasone-a potent corticosteroid with strong

anti-inflammatory effects-are being repurposed to alleviate the severe

inflammatory responses observed in critically ill COVID-19 patients,

potentially reducing mortality143. The anti-inflammatory characteristics of azithromycin,

an antibiotic, are currently under investigation for their ability to regulate

the immune system and mitigate inflammation in individuals with COVID-19144. Monoclonal antibodies, designed to specifically target

SARS-CoV-2, are hypothesized to neutralize the virus, offering targeted

therapeutic intervention.

Convalescent

plasma, derived from individuals who have successfully recovered from COVID-19,

contains antibodies that may neutralize the virus in infected patients, thereby

enhancing the host's immune response145. Antibiotics and antiparasitic agents, including

ivermectin, known for their well-established safety profile, are undergoing

examination for potential antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2. Additionally,

azithromycin, an antibiotic, is explored for its potential synergy with other

treatments in COVID-19 cases146.

Figure 5: The

illustration outlines the potential steps involved in the entry and replication

of SARS-CoV-2. The sequence initiates with the conformational change of the

viral S protein, triggered by its binding to the cellular ACE2 receptor. This

interaction facilitates the fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane

through the endosome pathway. The genomic RNA undergoes translation, leading to

the synthesis of the viral replicase polyproteins pp1a and 1ab. Viral proteases

then cleave these polyproteins, generating smaller functional products.

Following this, the viral polymerase transcribes irregularly, resulting in the

production of subgenomic mRNAs. These subgenomic mRNAs, in turn, contribute to

the translation of different viral proteins. During the assembly phase, viral

proteins and genomic RNA combine to form virions within the endoplasmic

reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. The ER-Golgi intermediate compartment

(ERGIC) plays a pivotal role in the maturation and transportation of virions.

Ultimately, assembled virions are encapsulated into vesicles and released from

the host cells.

9. Challenges and prospects

One major

challenge is the ongoing emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 virus variants. These

variants may acquire increased transmissibility, be resistant to immunity from

previous infections or vaccines and may lead to more severe disease. Monitoring

and adapting to these variants will be an ongoing challenge. Ensuring equitable

and efficient distribution of COVID-19 vaccines in itself remains one of the

major challenges. Disparities in access to vaccines can exacerbate the global

health crisis and hinder efforts to achieve herd immunity. Vaccine hesitancy

and misinformation continue to impede vaccination efforts. Promoting vaccine

education and addressing concerns is crucial to achieving widespread

vaccination and ending the pandemic. The long-term health effects of COVID-19,

also referred to as “long COVID,” are still difficult to understand. Some

individuals experience persistent symptoms and complications long after

recovering from the acute phase of the disease147,148. Healthcare systems in many regions around the globe are

still grappling with the strain of the pandemic. Treating severe cases of

COVID-19 can overwhelm hospitals and lead to delays in providing care for other

serious medical conditions. The pandemic has caused severe economic and social unrest,

Global cooperation and coordination are necessary to combat the pandemic

effectively.

Research

and development of booster shots and updated vaccines will likely continue to

address emerging variants and provide longer-lasting immunity. The development

of effective antiviral drugs to treat COVID-19 may improve outcomes for those

infected and reduce the severity of the disease. Achieving herd immunity

through vaccination remains a key goal for ending the pandemic. Encouraging

vaccination in underserved communities and improving vaccine access are

essential components of this effort149. The experience with COVID-19 underscores the need for

improved pandemic preparedness, early warning systems and global response

mechanisms to mitigate the impact of future infectious disease outbreaks. The

pandemic has accelerated the adoption of telemedicine and digital healthcare

solutions150. These innovations may continue to transform

healthcare delivery and improve access to medical care. Addressing the mental

health challenges arising from the pandemic will be a long-term prospect.

Investing in mental health services and support systems is crucial for

recovery. Promoting good hygiene habits and raising public health awareness can

be very effective in stopping the transmission of contagious illnesses like

COVID-19.

10. Conclusion

In

conclusion, COVID-19 presents a range of challenges, but there is also hope for

the future. Effective vaccination, treatments, global cooperation and

preparedness efforts can contribute to bringing the pandemic under control and

better preparing the world to respond to future health crises. The

comprehensive review provides an in-depth and enlightening examination of the

COVID-19 pandemic through September 2021. Millions of people have been affected

by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which has created previously unheard-of challenges

for global health. The review article elaborates on

several aspects of the illness, starting with its zoonotic origin and moving on

to person-to-person transmission, as well as a map of its geographic

distribution across continents. An important subject included in this research

is COVID-19's clinical manifestations, which may vary from modest respiratory

symptoms to severe instances leading to pneumonia, ARDS and multi-organ

failure. Examining the disease's impact on different age groups and vulnerable

populations, the article highlights the need for specialist healthcare

strategies to protect those who are most susceptible. The report also

discusses several COVID-19 diagnostic methods, including molecular tests like

PCR and antigen assays and serological testing for detecting antibodies. These

tests are necessary for controlling illnesses, tracking contacts and

establishing containment procedures. Investigated in the search for effective

therapies include repurposed drugs, immunomodulatory therapy and antiviral

drugs. The development and administration of vaccines are seen as crucial

strategies for halting the pandemic and promoting herd immunity. The article

acknowledges that COVID-19 comprehension and management have advanced

significantly, but challenges and hurdles still wait for the global healthcare

systems. The challenges include handling viral alterations understanding novel

varieties, combating false information and vaccination resistance and becoming

ready for impending outbreaks. The review provides a basis for further research

and information for public health activities and scientists working at the

molecular level, helping to decrease the consequences of the epidemic and

prepare for any future health crises.

11. Abbreviations

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute

Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome;

PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; HIV/AIDS: Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired

Immunodeficiency Syndrome; MERS-CoV: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus;

ICTV: International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses;

WHO: World Health Organization; PHEIC: Public Health Emergency of International

Concern; RNA: Ribonucleic Acid; CNS: Central Nervous System; RBD: Receptor-binding

Domain; RBM: Receptor-binding Motif; S: Spike Glycoprotein; E: Envelope; M: Matrix;

N: Nucleocapsid Protein; ORF1ab: Open Reading Frame 1ab; nsp: Non-structural Protein;

DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid; COG-UK: COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium; TMPRSS2: Transmembrane

Protease Serine 2; ACE-2: Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2; SP: Serine Protease;

S1/S2 site: Spike Protein Cleavage site; RdRp: RNA-dependent RNA polymerase;

CT: Computed Tomography; ACE2: Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2; T-cell:

T-lymphocyte; SP: Serine Protease; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration;

hACE2: Human Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2

The

authors declare that they have no discernible competing financial interests or

personal connections that could be interpreted as influencing the conclusions

made in this work.

13. Funding

This

research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public,

commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

14. Acknowledgment

Infrastructure facilities provided by the Department of

Biochemistry, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, under the DST (FIST &

PURSE) program are gratefully acknowledged.

15. CRediT

authorship contribution statement

Mohd Mustafa:

Conceptualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft

Preparation; Kashif Abbas:

Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis; Waleem Ahmad: Supervision, Data Curation, Investigation; Rizwan Ahmad: Data Curation,

Investigation; Sidra Islam:

Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing; Irfan Qadir Tantry: Funding Acquisition, Resources; Moinuddin: Supervision,

Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing; Md. Imtaiyaz Hassan: Funding Acquisition, Supervision,

Visualization; Mudassir Alam:

Data Curation, Formal Analysis; Nazura

Usmani: Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Formal Analysis; Safia Habib: Conceptualization, Funding

Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing.

16. References

12. Gralinski LE, Menachery VD. Return of the

Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses, 2020;12: 135.

49. Sit TH, Brackman

CJ, Ip SM, et al. Canine SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature, 2020;586: 776.

53. Liu

DX, Liang JQ, Fung TS. Human coronavirus-229E, -OC43, -NL63 and -HKU1

(Coronaviridae). Encyclopedia of Virology, 2021;428.